Battlefields and Monuments Portfolio

I thought that I would put together a portfolio of photos of battlefields and other war related things that I have taken in France and elsewhere. But mostly this is about French travel for the history buff. This is also a bit of a tribute to my grandfather, Robert Thibault.

These excerpts are from various travelogs I've written over the years. If they seem a little stilted in the way they flow, it's because they are from different trips, and I haven't had time to clean all of this up yet.

My Grandfather Robert Thibault (back-left with scarft) New Years Day, 1940, at the front lines. Yes, it was the Phoney War.

Photo by ?

My Grandfather Robert Thibault (left) and a friend, New Years Day, 1940.

Photo by ?

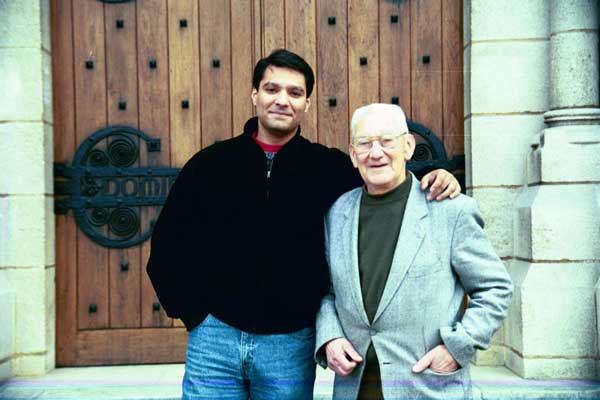

My Grandfather Robert Thibault and me at the Dorman WWI Chapel to French and German War Dead

Photo Lil Klein, 1993

To Know or Not To Know, That is The Problem

One of the most difficult problems in enjoying France is wondering where to begin and wondering what one will miss. In that sense, ignorance is bliss... If one is in doubt, and knows that there is much to see, then simply feigning ignorance to oneself can be beneficial as well as joyfully cathartic, though it is probably a little more self-revealing than one may wish for. This can also be embarrassing around friends and loved ones.

Another possibility that will frequently strike at the neurocenter of the intrepid traveler is to wing it. While the origins of the expression "winging it" appear to many to have become lost in the annals of the past, in fact, "winging it" means simply to take off in a prototype plane, all the while knowing that it is only held to the fueselage by two gallons of poor quality industrial glue - typically Elmer's or rubber cement - and two half-used rolls of duct tape left over from an era when Disco was king. A final side effect of the winging it approach to tourism is to read about something that one has walked right by - during the trip - just after returning Stateside or to wherever one's country or mental state of origin. This has frequently led to severe despondency and exasperation as revealed by this quote from Alfred P. Brehn of Elvinshire, Pennsylvannia: "You mean the Eiffel Tower was just one block over from our hotel the whole time?"

One of the most common questions tourists ask when reading this kind of a third person travelogue is 'why is this travelogue written in third person?' As a result, I will now shift to second person. Besides, by now, we kind of know each other, so why be so formal? Who are you again? And why can't I see you as I am writing this. Oh well, no matter. Please read on.

So for the above and for other reasons which can only be revealed properly by attending the Tourist's School of Hard Knocks (offered by AAA and by Michelin) you are advised to be a knowledgeable traveler.

Questions will abound... Questions such as "Why are there so many vowels in French words? How do the French learn to speak a language as difficult as French? Why do the French speak French when we could simply teach them English? What do the French call 'duct tape'? (They call it 'le duct tape'.) And, of course, why can the French write the sound "o" in so many different ways: o, au, aux, eau, ault, eaux, and others... In Lafayette, Louisiana, at Acadiana High School, our war cry was "G-e-a-u-x, geaux Rams geaux". Say it out loud and it will make sense. These questions, however, are irrelevant. The answers to these questions as well as the secret formula for making croissants and French Bread are closely guarded by the French Foreign Legion and the Daughters of the French Revolution. Of course, I can tell you if you ask me.

The first thing you should learn about France are about its pastries. Then you should learn at least 10 to 15 words of French. Most of these should be names of pastries. Or cheeses. Or wines, champagnes and liquors. Or yet other food groups. Of course, you may already know some of them: Brie, Bordeaux, Champagne, Dijon, Cognac, etc. French etiquette can also sometimes be rather baffling to the casual tourist. You should learn all of these and much more before going to France. After learning these few simple things and 132 others, you are pretty much ready to get down to the real business of figuring out what you are going to see and why!

BTW, I have come to the conclusion that it is impossible to design an efficient itinerary to see France. So I'll do my best with that huge constraint and just jump straight into different battlefields of France.

France As a Battlefield

France has seen armies come and go, fight, stop for "un cafe et un croissant", since before it could be identified as a country or even spell the word croissant. In fact, the croissant comes from Austria. The Austrians defeated the Turks at the Battle of Grand Croissants and instead of beheading the captured Turks - then called Ottomans after their famous chairs, broke into a spontaneous display of competitive baking, the winner's pastry being the crescent symbol of Islam, but that's another meandering tale. Queen Marie Antoinette - of "let them eat cake" fame, is almost universally overlooked for her great contribution to France - the croissant, which she brought from her native Austria. The Phoencians and Greeks founded the earliest still extant cities of France such as Marseilles and Nice. The Romans came in later and founded almost all of the major cities in addition to the ones founded by the Phoenicians and the Greeks. And I'm sure that I'm forgetting three or four significant cultures and civilization. So France is a great place to visit where the historian or the historical tourist can back through 2500 years of continuous history. One can go back even further to the caves at Lascaux and elsewhere to see some of the finest traces of prehistoric man.

So the Phoenicians, Greeks, and the Romans came, lived, fought, and frequently conquered. Who else? Well, the Gauls, of course, where the indigineous Celtic people. Their legacy and claim to fame lies in the Gaulloises Blondes cigarettes and Asterix comic books. Both are well worth their weight in moribund Francs or new Euros. The Huns led by infamous Attila left their mark too. The Moors briefly held almost half of France, or at least advanced to her center near Poitiers. Roland (Garros?) sang so poorly, as importalized in the "Chanson de Roland" that they ran away, terrified, never to look back. The Moors' strongest legacy may be the name "Maurice" which has lasted in French culture and also crept over to England as "Morris", becoming the name of a car company and also the main character in a hit Steve Miller song from the seventies. There were the Franks who stopped the Moors and who are claimed both by modern French and the modern Germans who gave their name to France. There is still a great mystery about whether or not they invented that great staple of Americana: Beans and Franks. There were the Normans from Scandinavia - or perhaps more precisely what is today Denmark - of 200 years earlier, who gave their name to the most famous province of France, at least for the annals of American military history and made sure that Normandy was famous over a 1000 years ago. They also conquered England. William the Conquerer hated England, only spoke French and returned to France to live and die. His descendants, for about 200 years, also spoke only French until their vernacular drifted through the linguistic silt of the local patois creating a new language known as Old English. In spite of its name, it wasn't limited just to old people. In fact, it became a pretty hip language and spawned some interesting literature, such as Chaucer's masterpiece "Canterbury Tales".

The English, thanks to land claims dating back to their Norman legacy, spent 130 years fighting in France before eventually getting pushed back out with the help of Joan of Arc. Who else? Off of the top of my head, I can also think of French religious wars, wars of expansion against other neighbors, the French Revolution, the War of 1812, the Franco-Prussian War, World War I, and World War II. And certainly there are many that I have missed. But each of these wars has left its trace in the fields and cities of France, and it is each of these that makes tourism in France so fascinating for the History Buff.

While WWII had many of its finest and saddest moments in France, France is just one of many countries which saw extensive combat and carnage and still bears scars of that great conflict. In WWII, the war was brought diretly to so many countries, including Germany, Russia, Poland, Libya, Egypt, England, Italy, Tunisia, Algeria, China, Yugoslavia and all of the other future Eastern Block Countries, Japan and probably another 20 or so countries. For the Pacific Theater, many of the battlefields and the evidences of war lay strewn across the Pacific.

But for that other Great War, WWI, the war was concentrated in two areas: The Western Front and the Eastern Front. And within the Western Front, most of the war was concentrated in France (and Belgium) with Germany almost completely unscathed by the war in any way except for perhaps a few minor aerial bombardments. For four great years, the war slithered back and forth across a 50 mile swatch of France that stretched from the English Channel to Switzerland. I can only imagine what it looked like. My guess is that the entire thing (no exaggeration) looked like one big gray mud-soaked field, bisected and disected by trenches, bomb craters, little supply rails, abandoned weapons and corpses. Visitors to several of the battlefields will be able to see remnants even today.

World War I

Here are some other images, mostly WWI related, from near where my family is from in France.

The WWI American Monument, Chateau Thierry

Photo Narayan Sengupta, about 1986

The official name of this monumnent, at least as listed on my map is "Monument Cote 204", and it's a kilometer or two to the south-west of Chateau Thierry. The town of Vaux is also nearby. On the other side of Autoroute A4 is the battlefield of Belleau Wood and another American National Cemetery.

I have no idea where this monument is. I have looked for it many times over the years since my Grandfather took us there around 1986. It wasn't more than an hour away from our house. There is a similar monument just north of Meaux on the way to Pierrefonds. There is also another similar one, the Monument a la Victoire de la Marne 40 kilometers due east of our home just north of the town of Sezanne.

Photo Narayan Sengupta, about 1986

The first thing that always strikes me when I see my Grandfather Robert Thibault is that he's so little. At 5'2", he's an amzingly small guy for the giant of a man he used to be. He still has powerful forearms, built the old-fashioned way through sweat and hard work, that are almost twice as big around as my own. His short snow white hair points straight to the sky in the fashion of a crew cut that has been his style since 1928.

I prompt him with one question after another, usually to get his voice on tape recollecting the stories that he has told me before. That's a bit of the problem. He knows that he's told them to me before and he leaves out most of the details, giving me the headline overview. "Tell me about WWI..."

"There was an aviation terrain here, with the big American fliers." He's referring to the rolling green field out in back of the house. Today all that remains is a slight undulation in the plot where the landing strip used to be. "I used to go there with my friends. We were all about 11." The rest of the story, which he kind of left out, was that they would go watch the "big" Americans with their shiny new aircraft. I always imagine the three of them crouching shyly behind some dune-like mound, watching the flyboys practice their marksmanship. One day one of the Americans asked my grandfather and his budies if they wanted to try to fire the big guns. Grandpapa said yes as did the others. The American warned him about the recoil, but that means little to an excited 10 year old who's never fired a gun. He did and the thing knocked him back to the ground. "Want to try again?" "Of course," grandfather responded; he never looked back after that. Like many Frenchman, he had a huge gun collection of match weapons that he used strictly for competition along with others that he used for hunting. I'm not sure why the French need so many guns, but they seem to have one for each occassion. I'm surprised that Benetton hasn't started marketing more colorful weapons. "Here, we have a dainty .357 magnum with an easy trigger for the most delicate high society women. Note that the barrel is fuscia." Then again, I suppose that if he happened to see a deer on the road in front of him, he could just reach into the trunk of his Citroen, rummage through the rifles in the back until he found the right calibre weapon. No use in wasting an expensive bullet when a medium priced one would do just fine. Later he got good enough to where he competed at both a national level and at an international level.

"Tell me about when Mrs. Roosevelt came to visit."

"It was at my Grandmother's in Mauperthuis." Mauperthuis is the adjacent town exactly 1.1 kilometers away according to the very precise French signposts. The architecture is the exact same as that of Saints and pretty much any other town: absolutely charming and virtually unchanged for two hundred years. It is so small that it makes Saints look like a megalopolis. But that town also holds a great deal of history including the chateau of D'Artagnan, also known as the fourth musketeer of the Alexandre Dumas stories. "Roosevelt's son's name was Quentin. He was killed when he was flying out here during the time that he used to come stay at my Grandmother's. Madame Roosevelt came to Mauperthuis, to France, and came to our house. There was an interpreter with her, and she wanted to see where her son used to stay. She came inside and looked at his room. There was a photo of him standing next to his aircraft."

"Did you ever meet him?"

"No, I can't say that I ever knew him," he said hesitantly. I had always thought that he had.

"How old were you?"

"I was 11 or thereabouts, until the age of about 14 or so. There was the airfield, with six airplanes; they were Cygognes." France still flies aircraft with the Cygognes (flying cranes) insignia. They are similar to the Flying Tigers in the way the locals venerate the celebrated Cygognes. The one other unit which is as well known would be the Sioux warrior-emblemed Lafayette Escadrille, with which many Americans served in WWI before the US joined the war. That group today flies nuclear armed Mirage 2000N attack jets, a far cry from the Spads of seventy years earlier.

WWI Chapel to French and German War Dead, Dorman

Photo Narayan Sengupta, about 1986

Chateau Thierry has a WWI monument to 1200 French and German soldiers in the form of a small chapel overlooking the river valley. The story is that the young men's bodies were so badly decomposed that they couldn't be recognized and nor could their uniforms. Thus they were burried communally without respect to their country or army. So while the living French and Germans fired away in a bloody war for four years, their fallen comerades sleep together for eternity.

My Grandfather and Lil at the WWI Chapel to French and German War Dead, Dorman

Photo Narayan Sengupta, 1993

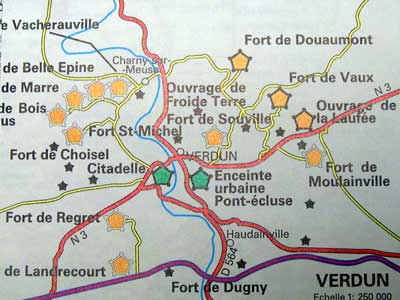

Left: WWI Cimitiere National, Verdun near the Fort de Douaumont; Photo Narayan Sengupta, 1996

Right: Detail of Verdun forts from IGN Map 907.

This cemetery, actually THE National Cemetery, is analagous to Arlington Cemetery in the U.S. However, unlike Arlington, it isn't just Frenchmen who are buried here, but also many Germans as well.

Once around Verdun, historians MUST visit the following: Fort Douaumont, the Tranchee des Baionettes, and the Underground Citadelle of Verdun.

Verdun is a city of walls wrapped within a castle enclosed within fortifications, to paraphrase the "mystery wrapped inside an enigma...". It's quite amazing. One has to wonder if armies held these towns just to hold them. I cannot understand what was the strategic significance of Verdun in and of itself. It's as if the French decided to create a point of strategic importance where there previously was none. Perhaps it was structurally reinforced to create an artificial military objective much in the way that Stalingrad was. The city that bore Stalin's name became a focal point during World War II in the same way that a pawn often does in a chess game, sucking up more and more of both Nazi and Soviet resources until it ultimately chewed up Von Paulus' 6th Army in 1942. Verdun was also a focal point of more than one major war.

Many of the ramparts are still extant as is the Underground Citadel (Cite Sousterrain). To me, it's not really an underground city as much as it is one built into the ramparts and one that is below the main part of the city. But the little "Verdun Decouvertes" brochure assures me that there is indeed a bonna-fide underground city, complete with underground galleries which can be viewed from the comfort of a "seat-car". French brochures can be humorous with their literal translations from French to English. Here are some examples from "Verdun Decouvertes": "Departures all 5 minutes". "Guided tour from the town..." Others include "Sell of tickets at the Tourist Office", "Passing there and through the lock Saint-Nicholas", and "Cruise the Current Downstreet". There are also some fun creative spelling errors, such as "backery". On the other hand, at least the French make an effort to accomodate English speaking (along with German, Spanish, Italian, Dutch, and sometimes Japanese speaking) tourists. What the brochure doesn't say is how this city, once a Roman town named Verodunum is also famouse as the site of the 843 Treaty of Verdun which divided Charlemagne's Holy Roman Empire into the fledgeling nation states that would ultimately become France, Germany and Italy.

There are extensive ramparts throughout the city which look like they could still be used. France has a great history of massive fortifications, no doubt honed through many years of being the most formidable European land power, and the walls are a constant reminder of how much warfare has been a major part of French foreign policy.

Later I pass a monument for Andre Maginot Line, another famous creator of fortifications whose work I plan to visit on this same trip. With so much still to see, I pass by it.

Now I'm winding my way north to Duoaumont, my main objective in coming to Verdun. It's not really in Verdun itself, but several winding and scenic kilometers away. The road-signs indicate the Memorial of Verdun, which is closed for the winter season. Everything is damn closed. Why the hell is everything closed. They didn't shut down the war for the winter. Imagine being ankle deep in muddy trenches, cold, without creature comforts, without good food, or possibly even without any food at all. Where did they go to the restroom? Imagine sleeping out here, every night, for months, or even years on end. It's no surprise that the soldiers often hated the their enemy counterparts then the generals who commanded from the comfort of near-by villages, housed in well-equiped officer's quarters. What could morale have been like? What could it have been like to be wounded, stuck out in no-man's land, wondering which would claim you first, the mortal wound or the freezing weather? WWI is mostly about killing, blood-shed, new weapons such as gas, fighter aircraft, and tanks. And of course, WWI is also about a generation of young men being bled to death in north-eastern France and in Czarist Russia. But WWI had its happier moments too, when enemy soldiers would put their weapons down and prettend that they weren't fighting. Sometimes they would share food or Celebrate Christmas together, French and German or English and German. One of my favorite WWI stories is about how some British and German soldiers, staring at each other across No-Man's Land, got together for a friendly game of soccer. Playing must have temporarily brought some semblance of civilisation, of what life should really be all about, back to them. An aircraft, not knowing what was going on below, strafed the make-shift field sending the soldiers scattering back to their respective trenches. Paul McCartney made a video based on the story. In the video, the two officers, watching the game from the sidelines, each shows the other the photo of his wife. When the aircraft circles overhead and starts firing, the two officers scatter with their men, and each ends up with the photo of the other's wife. This is when the memorial should be open, when it's bleak, cold, wet and overcast. That way tourists will appreciate the sacrifices made by previous generations. Probably if enough tourists did come through here, they would go away with the impression that war is hell. In any case, anyone not sympathetic to the plight of the soldier tucked away in the trenches should read Erich von Remarque's masterpiece "All Quiet on the Western Front". What a miserable, lousy, useless war.

To me, when I think of Europe, I think of WWI as the end of innocence and the end of European global hegemony. WWI seems to be the first war where any form of decency was thrown out the window. That isn't to say that war is anything other than barbaric at any other time, but this time there was a bitterness that could only have led to WWII . The war started decisively but finished rather inconclusively. France and England and the United States left the Treaty of Versailles as the main victors. But they had only barely won. Russia was in shambles, the Czars executed. Germany was in economic ruin and would be even more so when she was forced to pay for the damage she had caused. But the France and her allies had won a pyrhic victory. France had been bled white in terms of human lives lost, in terms of physical and fiscal destruction. WWI was the end of France as one of the world's true superpowers. From then on, she would be one of the second rank powers, behind the U.S., England, Japan, and later Germany and the USSR. The country that had seen glory days under Louis XIV and Napoleon was barely recognizable as much more than a tattered wreck of its former self.

WWI started out of a small spark, the assassination of the Austrian Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo by a Serb nationalist named something Princeps. A series of entangling alliances ensured that when Austria Hungary mobilized against Serbia, Russia would come to Serbia's defense. This was followed by a German declaration of war against Russia which in turn lead to France to declare war on Germany and vice versa. The Germans mobilized against France and sent troops into Luxembourg and informed Belgium that German troops would be traversing that little country to do battle against the French. This was a violation of Belgian neutrality which had been guaranteed by France, Germany and Great Britain in the Treaty of 1839. The English, determined to protect tiny Belgium, declared war against Germany. The grim reaper's task had been set in motion. Turkey joined Germany and Austria Hungary to form the Central Powers. Italy and Japan, future adversaries of Great Britain and France in WWII joined the Allies. Four years later, so did the U.S.

"When France went to war in August 1914, the French people almost without exception rallied to the defense of their country, setting aside the bitter class and political conflicts of the preceding decades. The German armies marched across Belgium and into northern France and advanced to within a few kilometers of Paris before being turned back in the Battle of the Marne in early September. They withdrew some 50 to 100 km (30 to 60 mi) and entrenched themselves on a line running from the English Channel to the Swiss frontier, deep within French territory.

During the next four years military operations on the Western Front were essentially efforts to break through the opposing trench lines and resume a war of movement. The machine gun and heavy artillery favored the defense, and attacks usually gained only a few square kilometers at a frightful human cost. By the end of 1914 France had lost 300,000 dead and another 600,000 wounded, captured, or missing. The defense of Verdun alone cost 270,000 French lives in 1916. After the bloody failure of the spring offensive in 1917, some French units refused to move into front?line positions, and the disobedience spread to more than half the French divisions. At the same time the security of the home front was threatened by war?weariness, strikes, and growing demands for a negotiated peace. General Philippe Pétain took command of the army and by a wise combination of punishment and concession restored discipline and morale. At home a new ministry headed by Georges Clemenceau silenced defeatists and renewed the will to continue the war.

In July 1918 a unified Allied command, the entry of large numbers of American troops into combat, and the attrition of the German war machine enabled the Allies to mount an offensive that forced the German government to ask for peace. On November 11, 1918, the newly established German Republic accepted an armistice and on June 28, 1919, signed for a formal peace treaty. France recovered Alsace and Lorraine. The German army was limited to 100,000 troops, a strip 50 km (30 mi) wide on the east bank of the Rhine River was demilitarized, and Germany agreed to pay reparations for damage done to French civilian property. France was the great Continental victor in the war, but at a staggering cost. About 1,394,000 men, a quarter of all Frenchmen between the ages of 18 and 30, had been killed, and the northeastern departments were devastated."

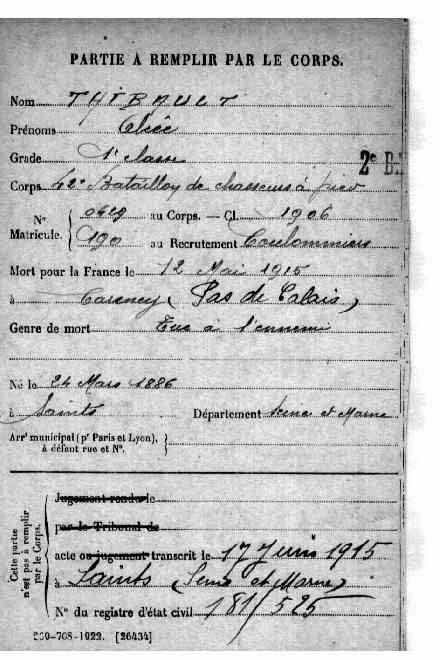

My family lost my great-grand uncle Alcee Thibault. To me, he's just a name on an obelisk off of the Grand Rue in the village. I've never met any of his descendants or his widow. I wonder if he knew that he was going to die when he went off to war. Perhaps a premonition told him that he would never return to see his family. Perhaps he laughed to himself as he lay dying on the battlefield, telling himself that he knew that he would end up this way. Or perhaps he died in pain, abandoned, lonely and frightened, wondering if anyone would ever find his body. Hopefully he died right away without knowing what hit him. That's the way I would want to go if I were in a bloody war like that. I knew that I would ask Grandpapa more about him once I got back to Saints.

Nov. 2003: I visited my great-grand uncle Alcee Thibault's tomb in the cemetery in Saints. He died during WWI on May 9, 1915 at Carency. That rings a bell, but maybe it's just because that's a generic sounding French town name. Was there any WWI battle there? Well, obviously there was a battle, or at least a hospital there, but was it significant, or was it just some kind of skirmish or something? I never even knew when and where he died (other than he died in combat during WWI in France) until last week when I saw the place and date on his tomb. I had always assumed that he had been killed in the Marne. My friend Carl Ankerstjerne turned this bit of interesting research up for me from The Battle of Aubers - 9th May 1915 Carl also let me know that Carency is located about 16 km (10 miles) North of Arras, 3 km (2 miles) West of a town called Souchez.

The French Army on 9 May 1915

"Attacking at 10.00am on 9 May, the centre Corps (XXXIII under General Petain, on a 4-mile wide front) completely overran the German trench system and pushed more than two miles onto the heights of Vimy Ridge. Joffre's reserves were too far away to exploit this success, and the infantry began to out-reach the range of its supporting artillery, giving time for a German recovery; the battle soon returned once more to close combat and entrenched positions. Intense fighting continued for a week, with particularly bitter actions on the Notre Dame de Lorette heights that resulted in the French capture of Carency and Ablain St Nazaire. The French advance did not quite achieve the capture of the crest of Vimy Ridge."

Update: Thanks to this web page, I have met my third cousin - Sylvain, who is Alcee's great grandson and learned more about Alcee's widow, etc. He helped me correctly identify this photo, which I had thought of as my great-grandfather Henri Thibault as actually his great-grandfather, Alcee Thibault.

That's my aged grandmother Cecile Thibault's handwriting scrawled across the top right. It reads "Thibault Alcee frere de Henri Thibault". She must have written it a year or two before she died perhaps in hopes that I would run across it. She identified a bunch of other family photos as well. Bless her for doing so.

Then there is this follow up image I found online at a French military source. It's Alcee's death information:

The Duoaumont Ossuary looms in the distance, a battle-ship grey silhouette 1700 meters away. The tomb looks like a surfaced submarine sporting an obelisk like conning tower, centered and half as tall as the cemetary is long. On the way to the ossuary, I pass a little chapel off to the left called "Notre Dame de L'Europe"; it marks the former village of Duoaumont, brutally wiped off the face of the earth by the great conflict of 1914 to 1918. The little mounds surrounding the chapel and covering the area that probably used to be the village remind me of trenches, which perhaps they were.

I drive up to and around the building of the massive granite ossuary which sits at the crown of a large, somewhat flat hill. It would be hard to mistake this as anything other than a cenotaph of some sort, especially one associated with war. At the same time, the edifice takes inspiration from other elements of French architecture and perhaps what the French have imported from the Egyptians. It is perfect for what it represents. The submarine like base is evocative of bunkers and turrets used to house cannons. The conning tower has elements of a chapel and is flanked by huge, but easily missed Roman crosses, sculpted into either side. On the other hand, it is strangely unfamiliar and out of this world, like something we would expect to see in a Star Wars movie. The white lines of the parking lot surrounding the building mimic what one really comes here to see, the rows and rows and rows of crosses. They are neatly arranged, grouped in squares of perhaps 15 rows and I don't know how many columns on the flat hillside facing the Memorial that I just left. There are 130,000 of them here, perhaps interspersed with some Stars of Davids, of both French and German soldiers. Arlington Cemetary outside of Washington, DC seems to go on for miles and rolls over hills and is punctuated with gently rolling roads which follow the natural contours of Robert E. Lee's former estate. This cemetary doesn't. It is the largest military cemetary of the many that dot the French country-side , but there is a certain brevity which is accented by the the tightly packed crosses. To me, all 130,000 markers cover an area less than that of two football fields. 130,000! That's more than five times the current population of Verdun. Astounding. I could run from one end to the other in about 90 seconds if I had to do so, but of course, there is no need or desire to do that. And even if I tried, I wouldn't get that far since I know that I'd have to read names. Clouds rolling in 100 feet overhead, the mausoleum on one side and trees on the three other sides of the field of crosses form a virtual hall to the dead. It is hard to comprehend why people would sacrifice themselves for their country so easily. How can the generals just throw away lives to become cannon fodder or to absorb bullets from heavy machine guns? Walking around and lingering makes me appreciate that I haven't been called to defend my country. It's something that I would do out of patriotic duty without a moment of hesitation, but it's not something that I would necessarily want to do for a pointless objective or a silly premise. I think that I would be tempted to negotiate as much as possible. Of course Neville Chamberlain has shown that negotiation to achieve "peace in our time" is not always a good idea, even if it is rather expeditious and easier than open conflict. Cold rain rounds out the picture, changing from a foggy drizzle to a bona-fide shower just as I get to the car and throw my camera on to the front seat. If my hair was long enough, it would billow in the wind just before it got soaked. But now it's too short, so in this case, it just gets soaked.

A beautiful piece of irony is the monument to the Jewish troops, French and probably also German, who died on behalf of both of their respective countries during WWI. Their numbers are small in comparision to the other dead, but that ratio would change starting just 20 years later.

I decide to leave the ossuary to find the nearby "Tranchee des Baionenettes", a monument built around the trench where a group of soldiers was found buried alive, with only their bayonets protruding from the ground.. Today wooden white crosses under a bunker like crypt mark the spot. These are the kinds of stories that arrouse passions and inspire other young men to get sucked into the malestorm that is war. Civilizations come and civilizations go, but here all of humanity was further defiled to some extent. In the time of the American Revolution, such an event would have precipitated war, but here it is a lonely footnote, forgotten by all but a few. But this is what war is really all about, the forgotten ones, the ones who will never make it home and perhaps won't even be identified..

At each of these battlefield monuments, I'm the only one braving the cold. For better or worse, I have the whole place to myself. And it feels more "authentic" as well; I feel more emphathy. After all the troops were miserable, continuously in the elements and standing in varying depths of mud most of the time - day or night I suppose. Occassionally, the yellow headlights of an older French car pass by, but for all practical purposes, I'm all alone, alone with my thoughts. For some reason, this solitude makes me wonder whether or not we've done a good job of archiving the thoughts of those who did survive the war. I guess that generation that must have been 18 or 19 at the end of the war is now about 95. The ones who were that age at the beginning of the war are now about 100 years old. How many more can there be who are still alive with all of their facilities intact? Those were just the youngest. The officers and the commanding generals are probably, almost without exception, all gone. Certainly all of the leaders of the countries involved died long ago. Have we done enough in archiving what they thought, what they learned, what they knew, what they would have done differently? So many have been reduced to nothing more than a name on a bronze plaque or perhaps a name carved in stone in some forgotten cemetary. And so many more didn't even get that kind of status. They are the unknown soldiers, with just a simple cross to mark them, their sole legacy in the world. Is that what life is all about? To just live 19 years only to die on some battlefield and then buried as an unknown? I guess that in 10 more years it will be the WWII generation that will be gone; will we have recorded enough of their thoughts?

Perhaps one of the sadest and most poignant reminders of the war is that Duouamont is not alone. In addition, there are two other cemeteries that I have seen on leaving to go back toward Verdun that aren't as big, but are probably on the order of 20,000 or more dead soldiers in each. Verdun, the city that is of ramparts, underground citadelles, battlefield cemeteries now calls itself "Cite pour la Paix", or, in English, City for Peace.

Compeigne - Clairiere et Wagon de l'Armistice

Armistice Memorial. The Wagon and small museum are off to the right.

Armistice Website

N31 led me to Compeigne just like it was supposed to. I sped up as I realized how close I was cutting it to the 12 noon closing time, and I didn't want to wait around until 2 pm since I still had to get back to Saints later that afternoon. By the time I made it to the Armistice site, seven kilometers before the city, it was noon, but the museum wasn't open anyway since it was Christmas. Instead I walked alone in somber reflection at what a quite emotional it must have been as the Germans came to Marschal Foch and signed the surrender documents. Foch intentionally chose this remote site in the forrest just because it was isolated and because both German and French railway cars could be brought to face one another like ships preparing to fire broadsides at one another. But it wasn't to fire at one another, but rather to offer a quiet peace away from the humiliation of public view.

This gesture was lost on Hitler who, when the Germans occupied France once again just 22 years later, blew up the French wagon and danced his famous victory jig in open glee.

Saumur

For more information about this great tank museum - including hundreds of tank photos, click on Saumur Tank Museum.

The lovely town of Saumur has a terrific tank museum, one of the best in the world. We caught the sunrise as we drove along the river, though we were in half-darkness for most of the way. The sun came up over the town just as we entered it. I dragged Janel to the tank museum, perhaps the foremost one in the world. It has Shermans, Panzers, T-34s and much, much more.

World War II

10:56, the sun is out and I'm greeted by a rainbow as I head north up the highway leaving Thionville. Thionville's single-spire medieval cathedral brushes up against the highway. The vibrations of heavy trucks cannot be very good for the masonry, but it still stands, a testament to the genius of Medieval design, materials, and construction. Today's objective's are the Maginot Line, Luxembourg. Tomorrow, perhaps Bastogne and Trier.

The Maginot Line to modern historians is a reminder of the axiom that every defensive weapon will be overcome by a newer and stronger offensive weapon. It is also a reminder that most combatants in a war expect to fight their next war the same way. The thinking behind the 200 mile long Maginot Line was that WWI had been fought in trenches. Very well then, let the French build the world's most formidable trench, one that couldn't be succesfully assaulted. The French virutally forgot the weapon that they and the British had invented, the tank. Both the French and the British high commands ignored their own prophets of combined armed tactics; but the Germans didn't. Guiderian and Rommel studied the writings of Charles de Gaulle and Liddell Hart and refined them into what would become Blitzkreig...

Starting in late 20s, the French started building, digging deep into the ground and sinking multi-storied defensive bunkers, self-contained fortresses designed to take upto three months of isolation along a front. These bunkers housed 130 or more men, and were linked to one another by telephone, by train, and by underground corridors. All that was visible at the ground level were dragon's teeth, tank traps, barbed wire and steel turrets reinforced by concrete protruding here and there facing toward Germany and Luxembourg. The turrets would have contained weapons of death, cannons, submachine guns and snipers' posts. Many of the turrets could be retracted electrically back into the ground during heavy assaults or during aerial bombardments only to be raised back into position during the infantry assault. On paper, the line was indeed impregnable. If only it could have moved at will...

The Germans must have agreed with the French; the Maginot Line would be difficult if not impossible to defeat. But there was no reason that they couldn't invade Holland and violate Belgian neutrality to penetrate into France through the Franco-Belgian border. So they did, using a variation of the plans which had served them twice already during the past seventy years during the Franco-Prussian War as well as in WWI. The French, who had spent so much money on the Maginot Line and static defense, didn't have enough resources to make their army mobile enough, mobile though it was. Such a weakness meant that when the Germans were invading Poland in September of 1939, the French sat in their Maginot Line instead of advancing into and attacking Germany. When the Germans attacked nine month later in May of 1940, they used their tanks in vanguard divisions while the French generally used theirs in support of the infantry troops. One for one, French tanks were better on paper than their German counterparts. And the French did have three armored divisions - DLMs. But while both the French and the British generally dispersed their tanks to support their infantry, the Germans concentrated theirs into the famed panzer divisions, pretended to head into Belgium and Holland with most of their force, let the Allies advance to meet them, then cut behind through the Ardennes - the junction between the mobile allied forces racing to the north and the static ones manning the Maginot Line. It wasn't that the Germans beat the French and the British head on, but rather even more cleverly struck behind and cut off supply for the British and French. The French had prepared themselves to rehash WWI. The Germans had learned from their defeat in WWI and decided to fight differently. In six weeks, it was all over; France had fallen in a defeat that surprised the world. The Maginot Line was eventually assualted and taken, but from the back, from inside of France. Even though it is a symbol of France's greatest defeat, it has fascinated me since I was a child. I can't wait to go see it.

A few minutes later I'm standing alone at the Ouvrage Immerhof of the Ligne Maginot. Interesting that it has a German name. I suppose that there are many legacies of alternatining bouts of French and German rule here in the two provinces of Alscace and Lorraine. This name must be one of those legacies. I also saw another sign off of the highway for another opening into the Maginot Line, so I suppose that much of the fortification must still be in existence, perhaps even the entire line even if no one still uses it. I suppose I'll have to go take a look.

A large solitary concrete bunker greets me. Obviously it's the back since it's visible and since it points away from Luxembourg. It's probably 25 feet wide and 15 feet tall, with the top five feet blending into the grass, so that from the other side, the entire fortress blends seamlessly into the hill. Circular rusted barbed wire gives a hint of how fortified this place must have been. Now it's empty, and as usual, I'm the only one. The back of the bunker is U shaped with the two arms of the U pointing out at me. A 10 foot deep waterless trench blocks enemy access to the bunker. As I approach a little closer, I see that the back of the bunker has a iron bar door as an entrance off to the right. A little iron bridge, three feet wide stradles the trench and gives access to the iron bar door. To either side are small openings through the concrete which are analagous to archer's slits but mean for submachine guns. There's a larger opening paired with the door but set to the left. I suppose that it's for larger guage weapons which have all been removed, as have the submachine guns, etc. I wonder how many lives were lost later in removing the mines to make the countryside safe once more. I once read that the British lost more than 200 soldiers while trying to clear their beaches of mines layed during WWII.

Fortress Immerhof, Maginot Line

Photo Narayan Sengupta, 1996

In front, there is a circular moat-like structure which is about ten feet across and equally deep. I have no idea how it could have been used since it could easily have been straddled by pretty much anyone. Perhaps there were mines on either side of the moat. But then why not just have more mines in place of the moat?

But my overall impression, at the risk of sounding blashphemous, is that it would have been pretty easy to take by determined foot soldiers. I suppose that much is now gone, and had I seen the fortification in its halcyon days, I would have been awestruck. How difficult could it have been for a determined group of German soldiers to have run up and tossed a grenade into one of the slits? Another thought that keeps bothering me is how could the French not have anticipated that the Germans would just mass their strength in one place instead of across a broad front? If the French put everything they had into the Maginot Line and the Germans put everything that they had into five good armored divisions and then made sure that their infantry was equally mobile, the Germans would only have to break the line and then pour through, the way water rushes through a breach in a dam. There would have been no way that the French could have held them back. Obviously the Germans thought of that too which explains their breakthrough tactics. Ah, to have the perfect vision of hindsight...

But it was certainly very interesting, and I'm now driving toward one of the other openings in the Maginot Line. The town I wind through has a street sign that says, "Cars slow down, the mothers request you to do so." I take note. I'm not speeding, but this will prevent me from doing so later on if I retain it long enough.

This opening already looks more impressive. I pass an observation post as I threat the Ford through the forest down the muddy unpaved road. There's a gate toward the opening. This one is called Immerholtz.

When I arrive I seee four men standing there outside the entrance. Their cars, a Citroen 2 CV, a Renault 4 and some others dating back at least several years along with the way they look and they way they are dressed, tell me that they aren't tourists with rental cars. They are standing huddled together barely at arms length talking about something that I can't hear. An older gentleman with white hair seems to be the leader of the group. His clothes are the nicest and his posture is the most formal. The other three are younger and look to be in their mid-thirties to mid-fourties.

Its probably closed, but let's see. "Bonjours messieurs!" I greet them, trying to sound as French as possible. Their staid faces break into smiles as they greet me back warmly. "Is it closed?"

"Ah oui, everything is closed for the season. We're just here for maintenance."

"That's too bad. I really wanted to take a tour of the Maginot Line. My grandfather told me that he visited it during the 1930s when he was a soldier."

"And where are you from?" The French always talk to anyone that they don't know in the formal "vous" form, so that to my plebian ears, it sounds like they might as well be saying, "And wherefore art thou from?"

"From Atlanta, Georgia in the United States. Have you heard of it?" I'm still in the habit of asking that since uptil it became the Olympic City for the 1996 Olympic Games, few in France had ever heard of it. I've been telling people that I was from Atlanta for 25 years, and always following that with "Do you know where it is?" or something like that. Old habits are hard to break.

They look at me in unison as if I were telling them one of the best known facts in the world, which perhaps it now is. "I just came from Paris since I arrived there two days ago, but I've always wanted to see the fortifications so I thought that I would stop by."

"Since you've come from so far away, we're not going to make you leave disappointed." The older man looks at the younger man in the blue maintenance outfit. "Will you show him?" Atlanta may have been the magic password. Then again, contrary to popular belief, the French, though more reserved then Americans, are friendly outside of the big cities. "Paris is just like New York," I usually explain to everyone Stateside. "How fair would it be if Atlanta were to be judged on the basis of New York?"

"Well of course. Come this way..." He gives me a warm smile.

"Be sure that you're out in fifteen minutes," the older one reminds my new guide. It's close to noon, and they are probably expected by their wives and families for lunch. We head inside and then down some stairs.

Gilles, as he introduces himself, is very nice, patiently taking me through every nook and cranny and showing me every passageway and every room while apologizing for only having 15 minutes in which to show me the mini-fortress. "This wasn't a main fortress. The main one is up on the hill nearby. I'll point it out to you when we exit. This was more of an observation post and was staffed by 130 soldiers. They would report back whatever conditions werre in efect right here. The telephones that they used to keep in contact with the headquarters still work. So does everything else. All of this is now close to 70 years old, but it all still works." We wind through one arched gallery off of which are the entrances to most of the rooms. At one end is a well. In one of the rooms is a large sistern, probably about eight feet in each dimension. "This was the water supply." Another room houses large pistoned engines which were the generators. Everything structural is made of concrete: the floor, the walls, and the ceilings. There isn't any decoration at all except for what has been added for the benefit of tourists. It is very comfortable down here. I had expected the concrete to make everything feel cold, somewhat like it is outside. But the earth makes a great insulator. For hot days, the air conditioning still works. The thickness of the concrete was designed to withstand bombardments by any known weapon of the day. Seventy years ago, this must have seemed like something straight out of science fiction. The place is incredible even now.

Gilles inside Fortress Immerhof, Maginot Line

Photo Narayan Sengupta, 1996

The bigger forts were up to six or seven stories deep, had movie theaters, libraries and more creature comforts. The French imagined the next war fought from this huge underground complex. War would be short since the wall would be impregnable. Never more would another generation of French boys be sacrificed to keep her land free of invaders. The leaders who built the Maginot Line forgot Napoleon's dictum of an army that stays inside its fortifications is beaten.

The two story high arched main hallway was used as a mess hall during meal time. Tables folded down from the wall on one side and iron benches from the other. Gilles turns the lights on in every room we enter. Surprisingly, all of the electrical components are original. He shows me the kitchen and the storage area for the military rations. The room seems to be way too small to store enough food for 130 men for upto 90 days. Gilles offers the following: "This wasn't the only source of food; the soldiers kept animals who grazed outside. As soon as combat started, the soldiers would slaughter the animals so that they would have a short supply of fresh meat."

The Maginot Line protected the entire French and German border which is the north-east corner of France. On the east, between France and Germany, is the Rhine River, an already formidable natural barrier. To that, the French added case mates and turrets of the Maginot Line. The rest of the line was even thicker and more heavily defended. The Belgian border presented a problem for two reasons: financial and political.

The French debated whether or not to extend the Maginot Line along the entire Franco-Belgian border. But this was deemed undesirable since it would imply that France was leaving tiny Belgium to itself in the event of another German invasion. It was a moot point since France really couldn't afford to further extend the fortifications. Instead the French tried to decide how to counter the Germans without any permanent fortifications. The answer was to meet the Germans head to head in Belgium as soon as the Germans invaded. The further in Belgium they met, the better as far as the French were concerned. But the Belgians found their hands tied since they were neutral. They could hardly give France permission to cross the frontier without being invaded from the other side. And the French would cross the border without first getting permission, no matter what the Germans did. This would prove tragic in the summer of 1940.

Gilles guides me through a munitions room and then a medical clinic which looks just like a dentist's office but with older equipment. The W.C. consists of a couple of key-hole shaped old-fashioned toilets and a channel like pissoir that runs along two of the walls. He turns on one of the spigots to show me that everything works. A ladder here and there leads up to one of the turrets. Each fortress was equipped with its own gas filtration system in case of German gas attacks, which were the scourge of WWI. The generator cranks up and I can hear the wheezing sound of air rushing throughout the room. The whole place smells of machinery. Big fat rivets attest to construction methods of the days before welding became popular. "All of this was built without machinery. It was all built by humans and pack animals." He tells me that the train only ran in the larger forts. I'm still not sure about whether or not the trains connected the larger forts or just ran inside them, though later I find that they were really small troop trains used internally only. The great cross section diagrams of the 1930s, depicting vast underground aircraft hangars, trains connecting all of the fortresses, etc., were just propaganda.

Retractable turret model, Fortress Immerhof, Maginot Line

Photo Narayan Sengupta, 1996

We go back upstairs and he shows me the defenders' perspective of the opening at the back. The French could fire submachine guns at anyone daring to attack; they could also drop grenades down a little chute into the dry moat outside. Unlike the other opening of the Maginot Line, this one's entrance is more formidable. The dry moat is about five feet across and is much deeper than the other one. Anyone going down into the moat would have had a hell of a time trying to get out.

Outside he shows me where the main fort was located; I can't see it, but it's up on the hill, hidden behind the trees. Gilles says that the French military still uses it. I guess that good concrete bunkers never go out of style, though some have been sold-off and demoted to serve as grain silos, etc. He points away from the main fort and into the forest. "You see that marker over there?"

"Yeah."

"That and many others all served as coordinates for the cannons up on the hill. The observers at this and other forts would stay in constant contact with the main fort, and then call in various coordinates as designated by the markers. The artillery would then rain down fire on the German tanks or infantry and then correct their fire upon further direction from the observers down here." When we get outside the fortress, I see that the other gentlemen have already left. The 15 minute tour ended up being half an hour. "And over here," he says, motioning to a little WWI vintage Renault tank, " is a tank we found buried underground with just the turret exposed. It was buried about three kilometers from here."

The tank was both rivetted and rivetting. It, like the fort nearby, was pretty much perfectly intact, a testament to the durability of thick plates of armor and to the construction methods of the first part of this century. I never did figure out how someone would use it and then get out if there was a ground assault. Whoever would have used it would have been killed with a well placed grenade.

He tells me that there are quite a few other forts in existence, but today this will be the last one that I see.

Business end of Fortress Immerhof, Maginot Line

Photo Narayan Sengupta, 1996

I thank him profusely for having made a special tour for me. "It was my pleasure," he responds with a big smile and a warm handshake. "Have a great vacation and Merry Christmas." I respond in kind.

A little later, I'm back on the highway after having followed Gilles out of the forest and through the town and after having bid him adieu one last time.

Of course one of the big jokes in the family is that punctuality skips every other generation, or at least it skipped Mom after having gotten Grandpapa. Another key difference between the two of them is that he is incredibly meticulous about where he puts everything. He is truly a creature of habit brought on by genetics and cultivated through years of being in control of everything that was his. He'll say that one of his attributes is that he listens to others and doesn't always assume that he is right. But that is outside of the house and outside of the factory. If anyone crosses his in either of those two places, then they're asking for it. I have that trait, but I cannot figure out if I got it from him or my father. One of my favorite habits when I'm in France is to get out of bed at around midnight, just after it has finally gotten all nice and warm under the sheets. The stained wooden stairs creak as I thread my way down, gingerly stepping on every third or fourth step to minimize noises that might awake others. I know the path of least noise, but I have never found a way to get down without at least two serious creaks. The landing is cold tile set on top of colder concrete. The landing puts me in front of the door to the kitchen which also opens with the loud clicking noise of the door knob turning. Inside the kitchen, one cupboard after another clicks when the magnets make contact as I go after croissants, chocolate, coffee and of course, bowls, plates, and spoons. My presence downstairs is always without evidence or witness, but the next morning, Grandpapa would always notify after I came down for breakfast with "I counted the bowls this morning. And I'm missing one. And also a little spoon and a plate." A simple mea culpa doesn't cut it. No, this daily ritual requires that I turn around, go back upstairs and procure the offending objects. Or at least it used to since now he's beginning to mellow and no longer admonishes me.

Anyway, with me he opens up and talks about family, the war, and other experiences. Unfortunately, the war comes up all to often. If it isn't WWI, then it's WWII. My generation is truly the spoiled generation since we haven't had one or two global wars to impact our collective pysches.

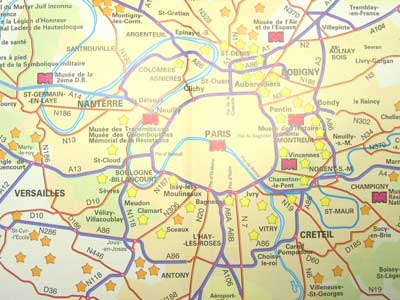

He starts off by talking about the time he helped someone else dig up someone who had been buried. They dug him up only to find out that he wasn't dead. "The big guy was still alive. Ah oui." I only caught the tail one of that one and decided to move on to other subjects. We stood over the Michelin map of France, completely unfolded and covering up half the table. The four of us could have been army generals plotting a campaign for the attack of France, which is only appropriate since the next topic on our agenda was World War II.

"Forbach... Saarbrucken. We could see across the frontier. We had the materials with which to do so." His fingers trace slowly across the map as he searches for the towns of his past, hesitating occassionally to ask one of us if the town he is pointing to is what he thinks it is. And he stops at other times to complain about how difficult it is for him to read these maps. His finger lands in the middle of the triangle described by Luxembourg, Metz and Saarbruken. "Boulay. Here. Next to it. So there was the river and between the river and the Boches and us, there was barbed wire. There were also little trip wires that would make noises to warn us of any intruders. We would exchange fire back and forth across the river. I didn't fire. I already had enough to occupy me. Eh bien mon vieux, one time at night we started firing at the noise, and it was a wild boar that we killed. But we didn't know what it was; we thought that it was the Boches." He reminisces continously about his friends from Germany of the post-War era. They are always friends, and friends first. He never even mentions the fact that they are German except by way of saying what city they live in. He references Kate and Otto at times around the dinner table, but he never calls them "my German friends" or anything like that. But when it comes to the faceless Germans during the war, it's always "les Boches", which is roughly analagous to an American war veteran referencing Hitler's soldiers as "the Krauts". Old habits die hard, especially anything which is stored deep inside his memory banks from that era.

"The little river here, next to the frontier. Bouzonville. We were at Bouzonville. Ah you know, it was something. The headquarters was at Thionville, and we were out in the nature. Alors, we were just at the end." He straightens up away from the table and turns to address me directly, as if giviing a lecture. The image of the general is now gone, replaced again by that of grandfather as a non-military person,the way it seems he's always been.

"I was in the 8th Division. [Note: This was apparently part of the French Second Army Group, French 3rd Army responsible for holding the Maginot Line from Montmedy to Strasbourg.] You had the Army Corps, underneath that the Division and then underneath that the Regiment. I was in the 12th Artillery Regiment. We had different unit types within the regiment. Foot soldiers, artillery, cavalry. Everything possible. Our guns were pulled by horse.

"Did you have horses or trucks to pull the cannons?

"No, no, no, we had horses. We were at fixed points, so mobility wasn't really possible; we never thought that the Germans would come there." Oh, ho, he laughs, a sad laughter of disbelief mixed with a feeling of foolishness that they were so easily outsmarted. "We were peaceful, but they came around and flanked us. They made the whole tour to come here."

"And uh, what was your title in the army?"

"I completed EORs, Eleve Officiers de Reserve" which must be the equivalent of a non-commissioned officer. "And so, if I had, after I finished the war, I went to do 15 day reserve periods at Armand(sp?), Reims, and we did maneouvers, etc."

"So for how long where you in the reserve?"

"About 40 years, at least. I finished my EOR exams, then I could go into either teaching or attend the great school of military administration, or there were others who had military careers. So I, when I was mobilized, I was twenty and a half. And I was a soldier at that time in '27. So there I was placed in to a regiment, the 12th Artillery, which I did for one year and a half."

"How many soldiers were there?"

"I don't know. There were nine batteries. There were those in charge of horses, those in charge of this and that. I don't remember. Perhaps 300 men? I don't remember."

"And how many were under your command?"

"I was in charge of my battery. There were nine in the regiment." The big ben chime of the wall mounted clock tries to interrupts our conversation, but he just raises his voice to be heard above the din.

"You had 45mm guns?"

"We had 75s." That the measurement is in milimeters is understood. "Because, voila, the 12th Artillery, was a battery of the 8th Division. The 12th Artillery was the light artillery of 75s, and the 112th Artillery had 155s, and we certainly didn't have any of those. The light artillery was in front, and the heavy guns with their longer range were in back. Yup, those were 155s." He shakes his head from side to side in a gesture that is either one of amazement at how powerful those guns were in their day or at how useless they were during the German onslaught.

"How many cannons made up a battery?" I always imagine about 10 guns firing in unison under command of an officer getting firing coordinates from air-based spotters. But then again, the French lost air superiority rather quickly in the six week campaign which crushed France.

"A battery, that was four cannons."

And how many to man each gun. Six?

Oh yeah, there was already one ot command the battery, then there were two aides, and I don't remember any more how many there were for all of the guns. But at each of the individual guns, there was a firer, a loader, one to aim" he laughs, "...there was a crowd, you know."

"And for you, which was the first day of combat?" I mean to ask him what was the first day that they fired their guns in anger, not September 1, 1939, the day the Third Reich spawned blitzkreig by invading hapless Poland.

"For us the first day of war was before the German advance. So, we would fire without seeing the other side. Actually, we observed each other with periscopes." He gestures indicating the kind of periscopes mounted on top of a tripod, but neither one of us can remember the exact term. "We watched the Germans who weren't even a kilometer away, like from here to Mauperthuis," which is the next town over from Saints.

"So you were taking pot shots at each other even before the invasion started." It was more a confirmation than a question.

"Yes," he replies emphatically, "it was before the invasion."

"This is in '39?"

"Yes, in '39."

"So when were you mobilized?" They had to have been waiting for nine months for combat if they were firing at each other in '39.

"On the first day."

"September 1, '39."

"Oui, oui."

"Did you go directly?"

"Oh no, what do you think? We were first sent to the Sarte (sp?) at Remans (huh?) And then we went to Sarget, a little town. And it was here that we had good cuisine and we ate well." He reminisces fondly. He probably hasn't talked about these experiences to anyone in quite a while. I always wonder what it's like to have all of this bottled up inside of him. "Here it wasn't the war. It was all a joke. But once we got to Thionville (just 20 kilometers from the border of Luxembourg), it wasn't the same."

"And when did you all arrive there?"

I don't remember all of my dates.

Approximately. About which month?

I don't know. September, no during the winter because there was snow on the ground.

When you guys would sleep at night, where did you sleep? On the ground?

Did you guys have tents?

"No, no, we made temporary shelters on the ground. Covered with the earth." I tried to imagine what that was like. It couldn't have been all that comfortable, but then that's what war is about. Send a generation of young men out to become cannon fodder. Many will die anyway, so why spoil them. Actually, many French units mutinied during WWI because they were treated so badly. Ironically, the Germans also almost mutinied and were aparently quite demoralized when, upon breaking through British lines, they found good food, wine, and plentiful supplies for what they couldn't get on their own side.

Did you sleep in the Maginot Line?

"Ah no, no, no, we never slept in the Maginot Line. But it was amazing. And huge. There was even a railway connecting different forts of the line." We trace more over the map to find the different towns where he was stationed. I get out brochures of the Maginot Line and show him on the map where I went and tell him about it. He looks stunned to see what I show him. "That's not the way we saw it. We didn't see anything since it was all underground. Only the turrets protruded from the terrain. We entered from the back and then the turrets were encased in steel. The cannons were raised in position when necessary."

"Yeah, I saw the models and the life size figures inside them. Yesterday, I climbed all over the fortifications. I went to the back. You know, for example, there was the opening at the back with the two turrets. And afterwards, there were little casemates for the submachinegunners, and it was easy to imagine the barbed wire, the dragon's teeth, and the tank traps that must have been there to prevent the Germans from getting through the line. And they showed me how the large cooridors had fold down tables on one side and fold down chairs on the other to serve as the mess hall at meal times." And I walk around the room making gestures so create an image for him.

"Oui, oui," he says in response as it all comes back to him sixty years after he last saw it.

"It was really very interesting. Anyway, getting back to what we were talking about. On the first day, effectively the day that you were mobilized, of course you didn't see any combat."

"Ah no. At night when we were there on the frontier, they would fire at us and we would fire back at them without seeing each other. We couldn't see them."

"But you saw each other from time to time, right?"

"Yes, because there was a forrest. And then it dipped and the Nied River was there."

"Did you ever call out to them?"

He seems incredulous. "But you couldn't. You were too far from one another, and we didn't want to be seen by them because they... Well if they saw you, then brrrrrp..." He pumps his fist back and forth like a piston so that I understand that submachine guns lined the river to pick off those showing themselves.

"What did you think of the Germans? Were they faceless guys or did you hate them or did you think of them as being just like you guys that just happened to be on the other side of the river fighting for the enemy?"

At first his response is emphatic, but then his tone changes to a more conciliatory one. "Ah oui. But you know, it doesn't do any good. There was a guy who was afraid of nothing. So one day he had to go to the water." He pronounces it like "What-air" as the French often refer to the toilet. "He got up and went to do his thing, and they picked him off. I think he died right away. So you can see, we really didn't try to communicate. We went down to a chateau named St. Creutzwald in the middle of the night, and had a funeral service, a mass, etc. And all of a sudden, the curee came forward and presented himself to me. It was a friend of mine from EOR. When I saw him, I said "Mon viex Trevilli" to which he replied, 'Ah mais dittes dont, c'est toi!' and we embraced each other like old buddies. I told him to stay with us. I said 'you're going to stay and we'll all eat. Just because there's a war on doesn't mean that we can't eat.' Later that night we all returned to Thionville." He's on a roll now, animatedly chattering as one thought flows to the next.

"After the war," he continues, "I had to go to Caen, in Normandy, to go see a brick factory. And the stuff I wanted was ready, but after that, I asked for the curee since I knew that he was from there. The lady told me that he was in the hospital. And I wrote afterward. I got news from him, but he had already died.

Normandy

WWII German Bunker, Pointe Du Hoc, Normandy

Photo Narayan Sengupta, 1996

Omaha Beach, Normandy

Photo Narayan Sengupta, 1996

June 6, 1944, the United States, England, and Canada, along with forces from Poland, France, Greece, Denmark and many other countries landed on five Normandy beaches, glided or parartrooped into several towns and set into action the most awaited Allied effort in the European theater. The invasion of Normandy is probably the greatest military assualt in U.S. history. It was one of the longest planned attacks. It was also one of the most important attacks since it opened the way for the liberation of France, Belgium, Holland and Luxembourg. The allied invasion of Normandy was in many ways a reversal of the German invasion of France from four years earlier. The statistics involved are staggering.

113 klicks to the old city that is Caen, the center of Normandy. Hitting the grey road at 11:22 am after waking up late at 10:30. It's been 1:30, 10:30, 2:30 and 10:30 wake ups the last four days. A little more erratic than normal. Perhaps the gods heard in my enthusiasm yesterday for the blue sky and the golden sun for this morning I'm greeted with a light dusting of snow on the ground and restless overcast skies. It's still France, and ergo it's still beautiful though even with this weather. Toll from Rouen to Honfleur is 22FFs for the priviledge to speed down A13 instead of more scenic two lane highways. Seemingly all to quickly I'm forced to cough up another 13FF for yet another toll. That's 35 for 115 kilometers. So that is about a buck for every 12 miles.

Verdun was "City for Peace". Caen, affected by war 20 years later, is named "Memorial for Peace". Memorials such as these are aplenty in a country which has seen so much recent violence.

Omaha Beach is next on my agenda. A bloody battlefield only 51 years ago, it has returned to its former serene state. At first glance, there is little to remind one of the horrors of war and of the greatest invasion in the history of humanity. The first thing I notice is the 27 hole Omaha Beach golf course placed on the bluffs high above the sea level overlooking the beach the same way German outposts did. Someone had a sick sense of humor. Of course, it probably does draw people to the beach who might not otherwise have come, and if that's what it takes, then I'm all for it. And I suppose that the French Government cannot just place the five great beaches off limits to everyone or at least reserve them as war memorials. If the government had to do that for every town, village, city, hedgerow, tree, etc., that had been touched by war, most of the country would probably be reserved as one kind of memorial or another. Nonetheless, it does seem to be more than a little flippant to have a 27 hole golf course overlooking the beach..

I keep following the frequent white and blue dove logo signs which are supposed to lead the way to different sites. But I see very little. Of course much of that is probably because everything is closed for the winter season

Dec. 27, 1995, 14:44 hours. Omaha Beach. It's the dead of winter, so it comes as no surprise that this place is one very cold windswept beach. But on a sunny day, the golden hues warm up what would otherwise be a sad, lonely and desolate place. Today it's sandy gravel and seashell coated narrow strip of beach, perhaps 100 feet across now. Gazing inland from the beach, like the GIs that came ashore 51 ½ years earlier, one's eyes are drawn past the narrow beach and up the sharp grassy hill that climbs probably 150 feet at close to a 45 degree angle. The Americans who hit the shore here encountered a fortified stronghold WN-62. There are nine other mini-fortresses here along this stretch of beach. WN-62 was a component of Hitler's Atlantic Wall, roughly analogous to France's Maginot Line.

The Atlantic Wall doesn't seem anywhere near as impressive as the Maginot Line, but then again, neither was it supposed to be. What it is, or was, was a series of heavily reinforced steel and concrete bunkers designed to house heavy cannons, communication posts, sub-machine guns, along with the manpower to train those weapons of death on anyone daring to come ashore on French soil. And of course, these same bunkers housed all auxiliary supplies for those same men.

Defense fortification WN-62 consists of about 12 concrete reinforced structures of varying size and varying height, which were for machine guns, 75 mm guns, kitchens, ammunition storage depots. The largest was the size of a small bedroom, probably designed to house the 75mm guns. Others were small, making me crouch to enter the holes in the ground that they were, and which afforded one a bare minimum of standing height while peering out of the slot to the beach below. The scary thing is that these bunkers don't look like they were connected underground. Some were, but not all. The men manning the little submachine gun posts would have been exposed to fire from the entire beach if they were to turn and run. Perhaps that's what the designers had in mind: positions that would force the gunner to stand and fight till death. Certainly many if not all of the defenders here died that day. It is bizzare to walk through these places knowing that someone has died, his blood, brain matter and guts probably splattered over the wall all around me. Now it's just little pock marks, vestiges of grenades tossed in here, that serve as mute witnesses to the Longest Day.

German Bunkers, Pt. Du Hoc, Normandy

Photo Narayan Sengupta, 1996

Strangely, I don't see anything that could have been a bunker or a place for them to sleep. So I'm not sure if the units that were stationed here slept here or slept nearby and were carted in as necessary. Or they may have walked here, but assumably, these positions were important enough to have been manned 24 hours per day. As I crawled in an out the remnants of these bunkers which faced out to the then gray sea, I realized how unprotected they really were. They were heavily reinforced, probably enough to withstand all but direct hits from the largest of bombs, but certainly these boys must have trembled and cowered in fear when they saw the US fleet coming, enough ships to change the horizon to metallic gray. Think about it; between Omaha, Utah, Gold, Juno and Sword, three million soldiers came ashore.

On the first day that they landed, something like 200,000 to 300,000 men landed, of which probably close to 50,000 landed here. I can only imagine, as I look at this beautiful blue sea dotted with fishing boats how startled the Germans must have been as they awoke to see this armada.

Ouistream, Arromanches, St. Mere Eglise, St. Marie du Mont and many other names will slowly fade from my memory just like they've probably faded from the minds of those who were here. But their legacy as stepping stones in the liberation of France and the eventual defeat of Germany will keep them on history maps for years to come.

The paratroopers dropped silently during the pitch black night, white parachutes colored that way so that they could be seen in case of emergency. The nervous ones were probably still practicing their French phrases on the way down. The paratroopers dropped onto fields, into the swamps, in ponds, into wells, into tress, into barns, on to church spires and pretty much anything else. Units scattered not able to find each other as they spread out in the dark. The metal crickets helped Allied soldiers find one another and identify friend versus foe.

St. Mere Eglise, Normandy

Photo Narayan Sengupta, 1996

At St. Mere Eglise, bucket brigades formed at 2:00 am to put out fires. Moments later, the paratroopers dropping in did so pratically on top of the German garrison and were cut to pieces. One soldier's parachute snagged on the church steeple. After struggling to free himself from his unlikely prison, he gave up and decided to play dead. He was one of the few that survived that drop.