Monitor and Merrimack

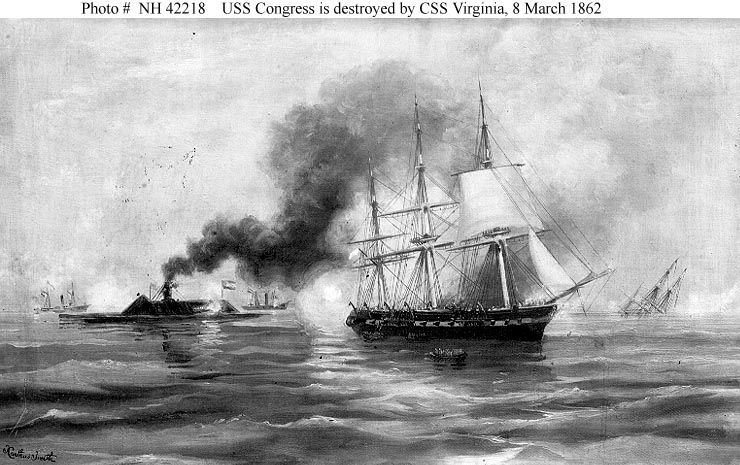

The Biggest Defeat in US Naval History

Note: unless noted otherwise, all images are from history.naval.mil.

Note: unless noted otherwise, all images are from history.naval.mil.

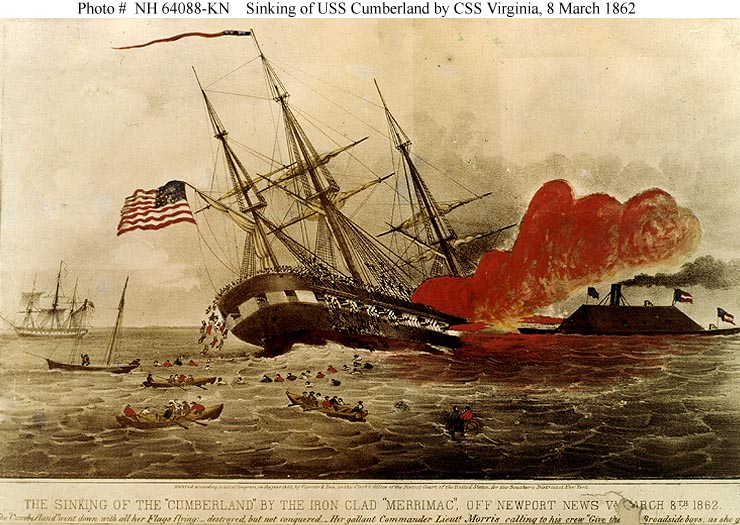

The Battle of the Monitor and Merrimack of March 9, 1862 is the most famous naval battle of the US Civil War and the first battle between ironclads anywhere. All but forgotten was its incredibly exciting prelude the day before, on March 8, 1862, when CSS Virginia inflicted upon the US Navy its greatest defeat prior to Pearl Harbor.

A little context helps, so here it is. Starting in 1854, the French had pioneered ironclads with her Devastation-class 18-gun batteries that were used with great effectiveness against the Russians during the Crimean War the following year. In 1857, they laid down La Gloire, the world's first sea-going ironclad warship. She was powered by steam, could make 11+ knots-per-hour and had 36 cannons. Their allies the British also joined the ironclad game with their own Aetna-class batteries that were copies of the Devastations and Warrior, an ironclad warship that was bigger, faster and stronger than La Gloire.

French Devastation-class; the world's first ironclads (Wikipedia).

La Gloire (Wikipedia).

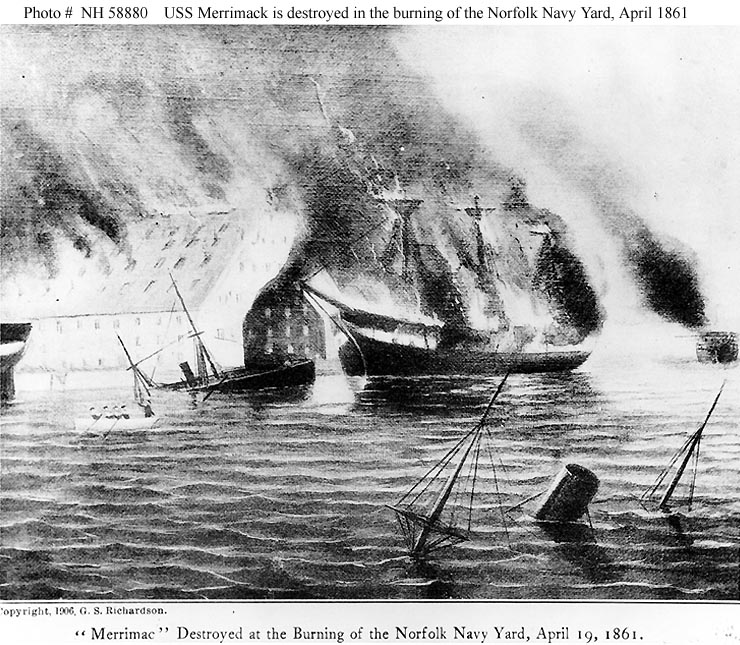

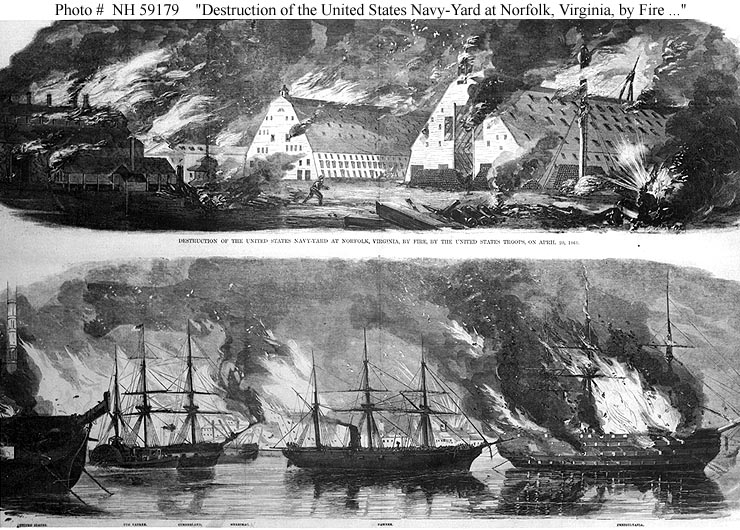

Back on this side of the pond, on April 12, 1861, the American Civil War began at Fort Sumter, South Carolina. Five days later, the state of Virginia left the Union and joined the Confederacy. On April 20, with cannon-armed Confederate troop at the gates, the small coterie of Union Soldiers left guarding Gosport Navy Yard in Portsmouth, Virginia, (near Norfolk) weighed their options. They were too few to be able to save all of the Union warships. The choice was simple: destroy them and the yard and escape. So they contemptuously torched any ship they could not sail out. Small fires were lit which turned into great ones. And for hours, Gosport was a raging inferno with giant flames and great plumes of sooty black smoke disappearing into the night sky. The fires extinguished themselves only when they found nothing else to burn.

Back on this side of the pond, on April 12, 1861, the American Civil War began at Fort Sumter, South Carolina. Five days later, the state of Virginia left the Union and joined the Confederacy. On April 20, with cannon-armed Confederate troop at the gates, the small coterie of Union Soldiers left guarding Gosport Navy Yard in Portsmouth, Virginia, (near Norfolk) weighed their options. They were too few to be able to save all of the Union warships. The choice was simple: destroy them and the yard and escape. So they contemptuously torched any ship they could not sail out. Small fires were lit which turned into great ones. And for hours, Gosport was a raging inferno with giant flames and great plumes of sooty black smoke disappearing into the night sky. The fires extinguished themselves only when they found nothing else to burn.

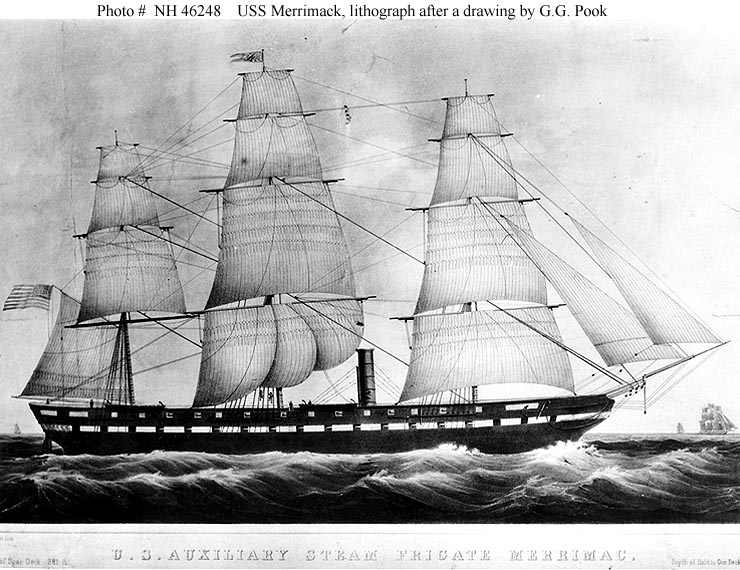

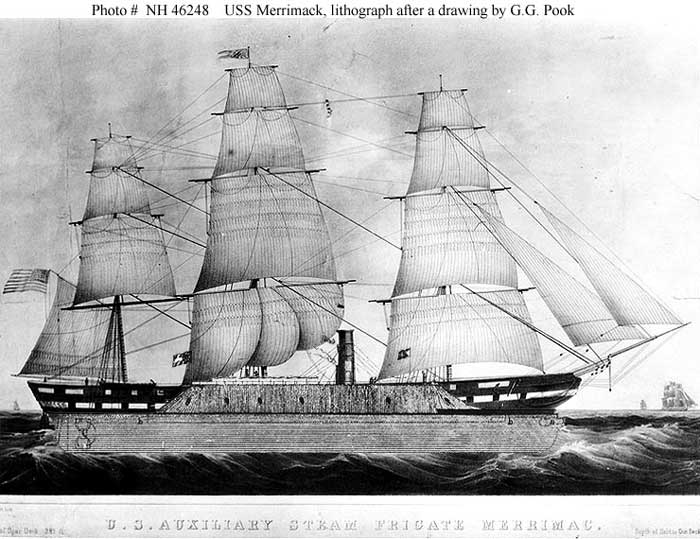

The most important casualty was first rate steam frigate USS Merrimack. She was one of six Franklin-class vessels, the US Navy's newest and most powerful warships. They were screw-propelled steamships good for 12 knots-per-hour on steam. They were also fully rigged to move under sail and had 38 cannons. Since commissioning in 1856, Merrimack had sailed the Atlantic, sailed the Pacific and had served as the flagship of the Pacific squadron. Now, though Merrimack's boilers had been lit in advance, she found that her only escape route was blocked: planning ahead, the Confederates had deliberately sunk light boats in the Elizabeth River's channel. Merrimack burned down to the waterline.

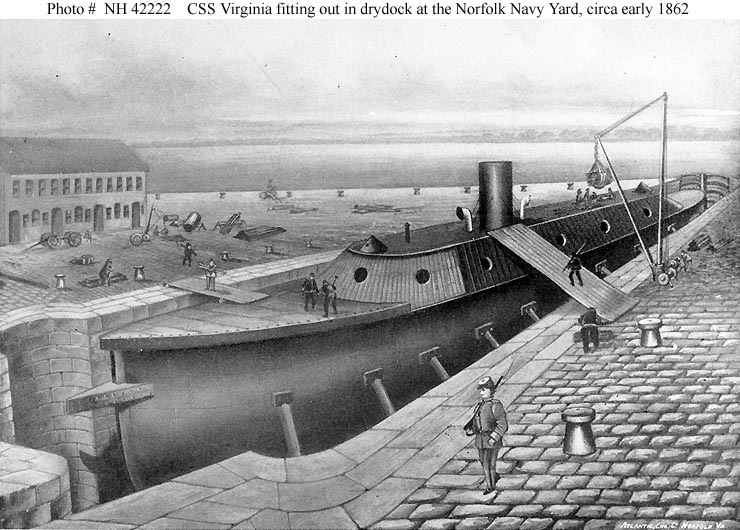

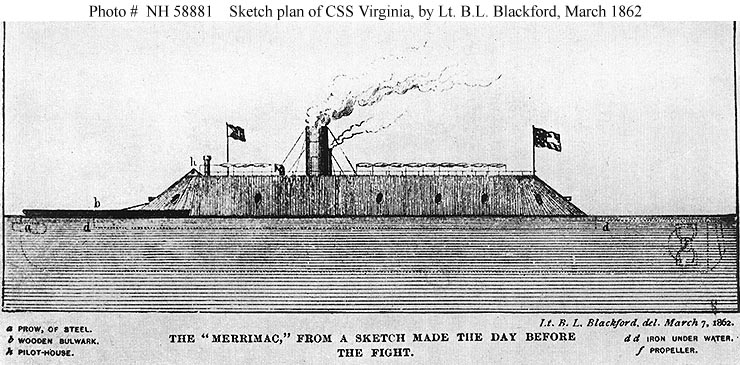

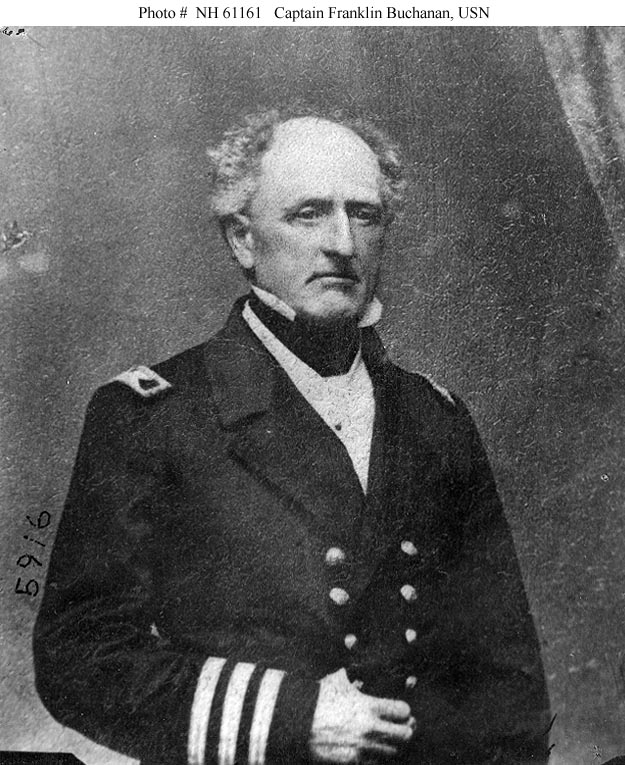

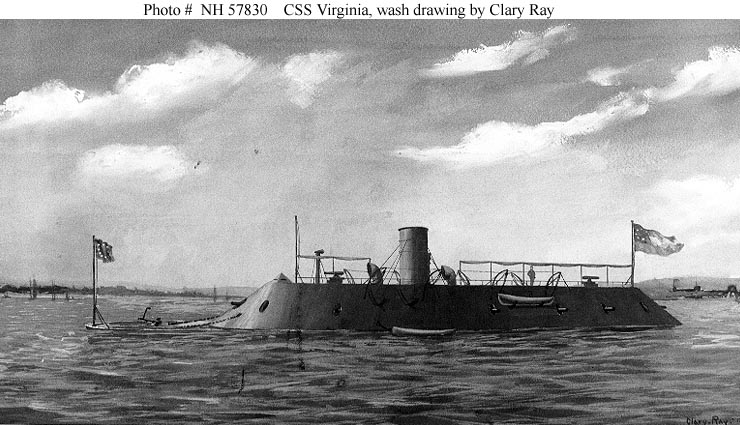

It took some imagination to even contemplate reusing what was left rather than scrapping it. However, the Confederates, low on resources and ships, were desperate. They were also ingenious. Inspired by the French and British, the Confederates raised and cleaned Merrimack's hulk. Magically her steam machinery and hull proved salvageable. They added six powerful 9" Dahlgren cannons, four smaller cannons and a solid four-foot-long, 1,500 pound triangular iron ram at her bow to stab enemy ships. But most interesting was her new 45-degree angled back casemate superstructure, protected by 4 inches of precious iron plating made of flattened railroad ties and under that, a solid two feet of wood. What emerged from the stunning transformation was an amazing new ironclad the Confederates rechristened CSS Virginia, but she is usually still called Merrimack. Commanding her was a highly experienced 61-year-old named Franklin Buchanan.

It took some imagination to even contemplate reusing what was left rather than scrapping it. However, the Confederates, low on resources and ships, were desperate. They were also ingenious. Inspired by the French and British, the Confederates raised and cleaned Merrimack's hulk. Magically her steam machinery and hull proved salvageable. They added six powerful 9" Dahlgren cannons, four smaller cannons and a solid four-foot-long, 1,500 pound triangular iron ram at her bow to stab enemy ships. But most interesting was her new 45-degree angled back casemate superstructure, protected by 4 inches of precious iron plating made of flattened railroad ties and under that, a solid two feet of wood. What emerged from the stunning transformation was an amazing new ironclad the Confederates rechristened CSS Virginia, but she is usually still called Merrimack. Commanding her was a highly experienced 61-year-old named Franklin Buchanan.

Using a little imagination and Photoshop, we can line up other historical drawings to compare the USS Merrimack to the CSS Virginia that emerged from her.

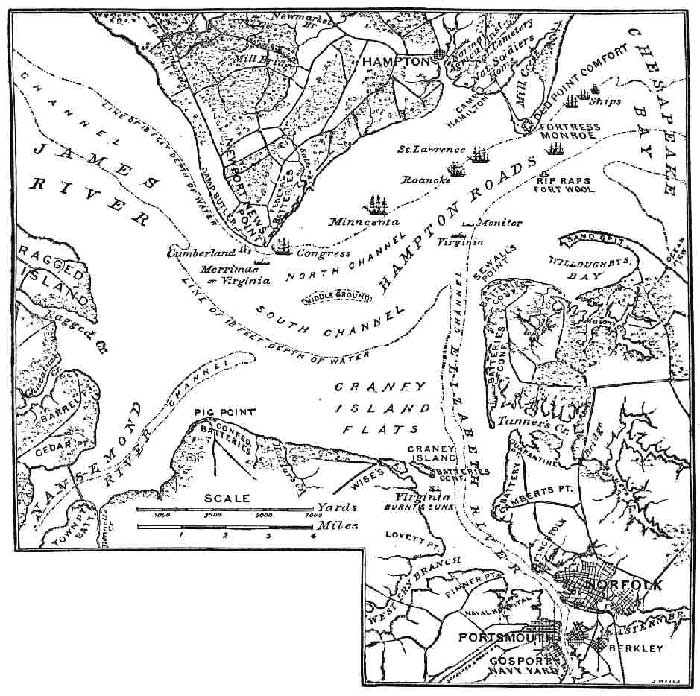

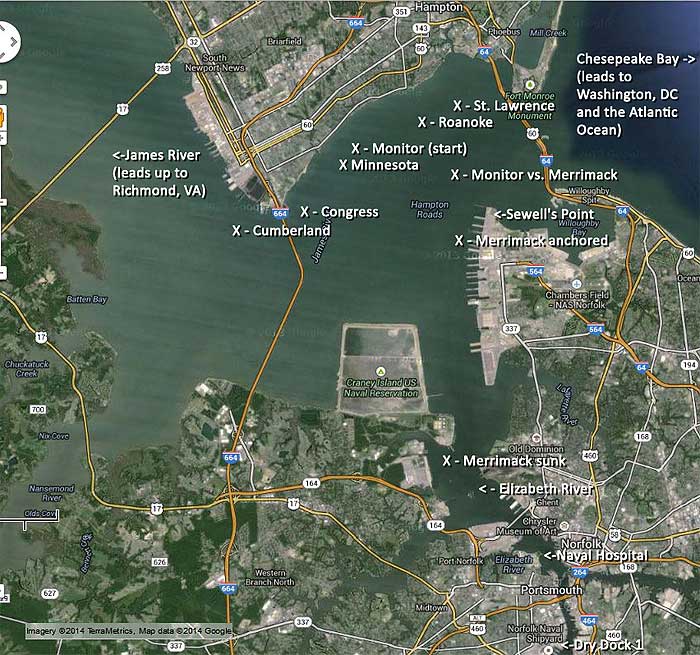

Portsmouth sat on the Elizabeth River across from Norfolk. At 11:00 am on March 8, Merrimack and five lesser Confederate warships cast their moorings, entered the Elizabeth River and sailed due north 10 miles into Hampton Roads, a five-mile-wide body of water fronting Norfolk that served as a four-way intersection between the Atlantic Ocean/Chesapeake Bay to the northeast, the James River and Richmond to the northwest, Suffolk and the Nansemond River to the southwest and, of course, Portsmouth and the Elizabeth River to the southeast.

Portsmouth sat on the Elizabeth River across from Norfolk. At 11:00 am on March 8, Merrimack and five lesser Confederate warships cast their moorings, entered the Elizabeth River and sailed due north 10 miles into Hampton Roads, a five-mile-wide body of water fronting Norfolk that served as a four-way intersection between the Atlantic Ocean/Chesapeake Bay to the northeast, the James River and Richmond to the northwest, Suffolk and the Nansemond River to the southwest and, of course, Portsmouth and the Elizabeth River to the southeast.

The Gosport Navy Yard is at bottom center.

Here is the same view today based on Google Maps; note landfill effects on the shoreline and the many slips for the massive US Naval Base at Sewell's Point.

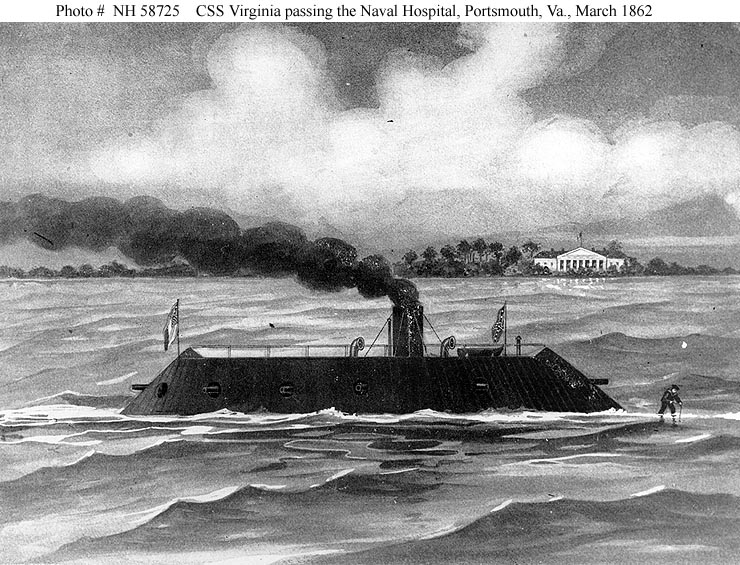

Merrimack sails north up the Elizabeth River. It's now two miles north of its drydock. Perhaps the man at the bow is looking for sandbars. The Naval Hospital still exists today, albeit surrounded by larger modern buildings.

Facing the Confederates were five first-rate US Navy warships Cumberland, Congress, Minnesota, Roanoke, St. Lawrence totaling 205 cannons and several smaller vessels. Ironically, Minnesota and Roanoke were Franklin-class ships, and thus former sisters of Merrimack. Union coastal forts facing Hampton Roads added over 70 cannons. Buchanan's ironclad had a rookie crew of 320 that had never fired her guns, and his ships totaled only 21 cannons, but he was hardly intimidated.

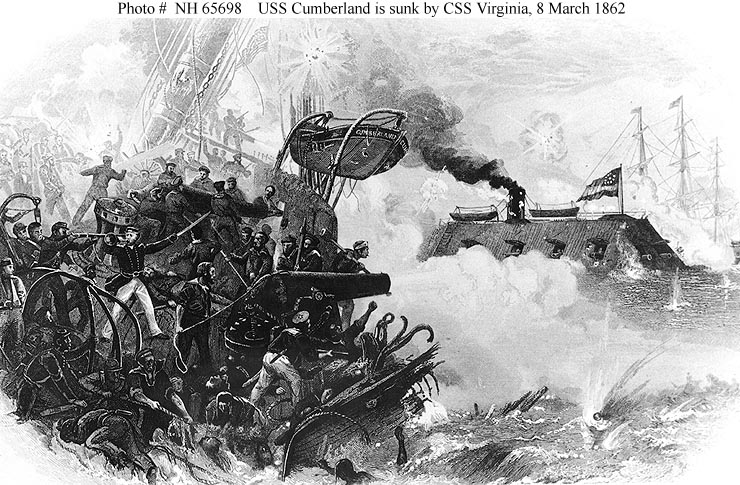

Though the opposing vessels first saw each other at about 1:30 pm, they still had to get in range. Time crawled slowly, as did Merrimack. It was 2:15 when the first shots boomed across Hampton Roads. Within a few minutes, Cumberland, Congress and the artillery battery at Newport News had engaged Buchanan's flotilla and Minnesota was dueling with Confederate guns at Sewell's Point. The Confederates "crippled" Minnesota's mainmast.

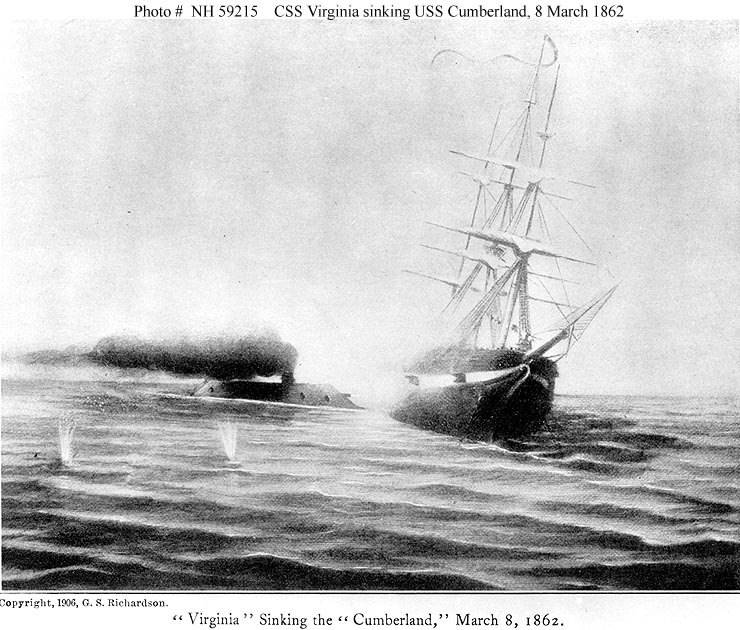

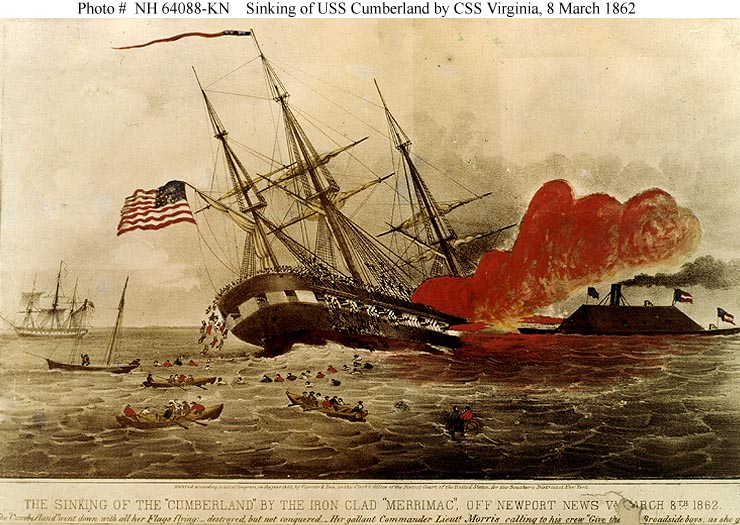

Merrimack's first target was Congress. Merrimack opened up with her bow gun, and then fired a four-gun broadside as she slipped by her toward the 24-gun Cumberland, her next target. Merrimack's draft was 22 feet, and the waters of Hampton Roads were shallow and full of sandbars and shoals hampering maneuver. Wishing to conserve his scarce ammunition, he pointed his ship straight at the Cumberland, and ordered full speed, which is to say, not very fast at all.

Bulked up with all of her iron, the transformed and overweight 3,200-ton Confederate monster needed 45 minutes and a mile to circle and could only make five knots, about as fast as a man could jog. But that was enough. She plowed ram first into Cumberland's wooden hull and bludgeoned a gaping hole large enough for a horse and carriage to drive through. Cumberland started to sink almost immediately, and this created a problem. Merrimack's engines weren't strong enough to back her out, and the ram wasn't breaking off. The Confederate ship was entangled with her prey, and appeared destined to sink with her adversary. Finally, Merrimack twisted free, leaving her ram knifed into her victim. Even then, Cumberland's well-trained crews held their posts and fired three broadside volleys at their enemy as she keeled over. The volleys did some damage, but failed to penetrate Merrimack.

Bulked up with all of her iron, the transformed and overweight 3,200-ton Confederate monster needed 45 minutes and a mile to circle and could only make five knots, about as fast as a man could jog. But that was enough. She plowed ram first into Cumberland's wooden hull and bludgeoned a gaping hole large enough for a horse and carriage to drive through. Cumberland started to sink almost immediately, and this created a problem. Merrimack's engines weren't strong enough to back her out, and the ram wasn't breaking off. The Confederate ship was entangled with her prey, and appeared destined to sink with her adversary. Finally, Merrimack twisted free, leaving her ram knifed into her victim. Even then, Cumberland's well-trained crews held their posts and fired three broadside volleys at their enemy as she keeled over. The volleys did some damage, but failed to penetrate Merrimack.

Merrimack engaged some of the Union coastal forts, silencing 20 cannons and sinking two small Union ships.

The 41-gun Minnesota retreated and at 3:20 pm inadvertently beached herself on a sandbar where it was too shallow for Merrimack to operate. Roanoke (40 guns) and St. Lawrence (50 guns) both ran aground too, essentially fleeing from the Confederate ironclad. Merrimack headed toward her ex-sisters, but also fearing running aground, she stopped a mile short of Minnesota, fired some shots at her ineffectively. St. Lawrence fired 74-shots in reply, but without effect. Though Merrimack wasn't damaged, she turned away.

Merrimack engaged some of the Union coastal forts, silencing 20 cannons and sinking two small Union ships.

The 41-gun Minnesota retreated and at 3:20 pm inadvertently beached herself on a sandbar where it was too shallow for Merrimack to operate. Roanoke (40 guns) and St. Lawrence (50 guns) both ran aground too, essentially fleeing from the Confederate ironclad. Merrimack headed toward her ex-sisters, but also fearing running aground, she stopped a mile short of Minnesota, fired some shots at her ineffectively. St. Lawrence fired 74-shots in reply, but without effect. Though Merrimack wasn't damaged, she turned away.

Next, Buchanan set his sights on the 50-gun Congress. The two vessels lashed at each other. Congress' guns did absolutely nothing against Merrimack's iron. But Merrimack's shots devastated Congress, making her strike her colors. By 4:00 pm, Congress was flying a white flag. While the Union vessel was surrendering, Union shore batteries opened up killing several and wounding Buchanan. Outraged, he ordered hot shell and incendiary rounds poured into Congress, setting her ablaze.

By 7:00 pm, it was getting dark. Tired, and worried about sandbars, Buchanan decided to anchor at Sewell's Point in Norfolk. For now at least, the combat was over. Buchanan was optimistic. He and his Merrimack would finish Minnesota the next day, and for all practical purposes, the Union blockade might as well be considered broken.

By 7:00 pm, it was getting dark. Tired, and worried about sandbars, Buchanan decided to anchor at Sewell's Point in Norfolk. For now at least, the combat was over. Buchanan was optimistic. He and his Merrimack would finish Minnesota the next day, and for all practical purposes, the Union blockade might as well be considered broken.

At 9:00 pm, a brand new Union ironclad named Monitor slipped into Hampton Roads after having set out from New York two days earlier. It took more than an hour to find a pilot who would brave the sandbars, dark currents and the idea of being in combat. So by the time she reached Minnesota, it was 11:30 pm. Then Congress blew up just past midnight pushing Union casualties to around 370 versus 24 for the Confederates. Buchanan had inflicted on the US Navy its greatest defeat ever, and Merrimack appeared unstoppable. However, the next day she would fight Monitor in the first battle between ironclads. But that is a story for tomorrow or just click Monitor and Merrimack, day 2.

Narayan Sengupta

Civil War Links

- Monitor and Merrimack, day 1

- Monitor and Merrimack, day 2

- Slavery Caused the Civil War

- More Civil War Causes

- Civil War Declarations of Causes of Succession of the southern states

Home

Home Hearts of Iron

Hearts of Iron

French Military Victories...

French Military Victories...