Robert Thibault - World War II French Soldier, 1939-1940, page 2

1939-1940: The Phony War/Drole de Guerre

"And for you, which was the first day of combat?" I mean to ask him what was the first day that they fired their guns in anger, not September 1, 1939, the day the Third Reich spawned blitzkreig by invading hapless Poland.

"For us the first day of war was before the German advance. So, we would fire without seeing the other side. Actually, we observed each other with periscopes." He gestures indicating the kind of periscopes mounted on top of a tripod, but neither one of us can remember the exact term. "We watched the Germans who weren't even a kilometer away, like from here to Mauperthuis," which is the next town over from Saints.

"So you were firing at each othereven before the invasion started." It was more a confirmation than a question.

"Yes," he replies emphatically, "it was before the invasion."

"This is in '39?"

"Yes, in '39."

"So when were you mobilized?" They had to have been waiting for nine months for combat if they were firing at each other in '39.

"On the first day."

"September 1, '39?" That was the day the Germans launched their rapid assault on Poland officially starting World War II.

"Oui, oui."

"Did you go directly?"

"Oh no, what do you think? We were first sent to the Sarte (sp?) at Remans (huh?) And then we went to Sarget, a little town. And it was here that we had good cuisine and we ate well." He reminisces fondly. He probably hasn't talked about these experiences to anyone in quite a while. The French can be so disorganized sometimes. In spite of years to plan for mobilization for a war many felt would come, the French soldiers were zig-zagged across France, being mobilized in one part of France, being sent to another to meet up with their units then being sent to yet another side. I always wonder what it's like to have all of this bottled up inside of him. "Here it wasn't the war. It was all a joke. But once we got to Thionville (not too far away from the corner of France and Germany and just 20 kilometers due south of Luxembourg), it wasn't the same."

Map of northeast France. Copyright IGN.

"And when did you all arrive there?"

"I don't remember all of my dates."

"Approximately. About which month?"

"I don't know. September. No (it was) during the winter (of 1939-1940) because there was snow on the ground."

"When you guys would sleep at night, where did you sleep? On the ground? Did you guys have tents?"

"No, no, we made temporary shelters on the ground. Covered with the earth." I tried to imagine what that was like. It couldn't have been all that comfortable, but then that's what war is about. Send a generation of young men out to become cannon fodder. Many will die anyway, so why spoil them? Actually, many French units mutinied during WWI because they were treated so badly. Ironically, the Germans also almost mutinied and were aparently quite demoralized when, upon breaking through British lines, they found good food, wine, and plentiful supplies for what they couldn't get on their own side.

"Did you sleep in the Maginot Line?"

"Ah no, no, no, we never slept in the Maginot Line. But it was amazing. And huge. There was even a railway connecting different forts of the line." The images of vast endless superforts - a non-stop belt of dome-shaped thick metal turrets and thick guns above the ground and multiple stories of vast underground stores, airplane hangars and underground trains was propaganda. I didn't bring that up.

The reality was impressive enough - gros ouvrage and petit ouvrage forts capable of housing 1,200 men and 120 men respectively. The Maginot Forts had massive poured walls and roofs of concrete reinforced by thick rods of steel, overpressured to keep out gas and impressive phone, toilet and plumbing systems. Their weakness seems to have been rather unimpressive armament. The best forts often had but a single 135mm gun and maybe two to four 75mm guns and a handful of machine guns.

But we trace more over the map to find the different towns where he was stationed. I get out brochures of the Maginot Line and show him on the map where I went and tell him about it. He looks stunned to see what I show him. "That's not the way we saw it. We didn't see anything since it was all underground. Only the turrets protruded from the terrain. We entered from the back and then the turrets were encased in steel. The cannons were raised in position when necessary."

Maginot Line - Immerhof - front

Maginot Line - Immerhof - rear

"Yeah, I saw the models and the life size figures inside them. Yesterday, I climbed all over the fortifications. I went to the back. You know, for example, there was the opening at the back with the two turrets. And afterwards, there were little casemates for the submachinegunners, and it was easy to imagine the barbed wire, the dragon's teeth, and the tank traps that must have been there to prevent the Germans from getting through the line. And they showed me how the large cooridors had fold down tables on one side and fold down chairs on the other to serve as the mess hall at meal times." And I walk around the room making gestures so create an image for him.

"Oui, oui," he says in response as it all comes back to him sixty years after he last saw it.

"It was really very interesting. Anyway, getting back to what we were talking about. On the first day, effectively the day that you were mobilized, of course you didn't see any combat."

"Ah no. At night when we were there on the frontier, they would fire at us and we would fire back at them without seeing each other. We couldn't see them."

"But you saw each other from time to time, right?"

"Yes, because there was a forrest. And then it dipped and the Nied River was there."

"Did you ever call out to them?"

He seems incredulous. "But you couldn't. You were too far from one another, and we didn't want to be seen by them because they... Well if they saw you, then brrrrrp..." He pumps his fist and forearm back and forth like a piston so that I understand that submachine guns lined the river to pick off those showing themselves.

"So what were your memories of the first day of being attacked?" I am determined to get the answer to this one.

"The day of attack? Well listen, we were in the grottes de la faux with our anti-tank guns which I had been given. The Boches were chasing us all over the place. And they were using their machine guns. The guys would duck into the the shallow trenches, but the Germans would just run their tank treads on top of them. So here when they bombarded us in the ditches, they fired from above. They guys wanted to flee. I told them not too saying that it wasn't the time and that they were just going to get killed as they made their way into the woods. They kept on bombarding. We made our way into the woods, toward Soissons.

The war ended rather quickly for my Grandfather. The first day the Germans hit their lines, which must have been not too long after May 10th, 1940, when the Germans attacked the Low Countries and France, it was bloody chaos. While my Grandfather's regiment and battery had 75s, they had just a few shells of the right caliber, which makes me wonder how much opportunity they had to actually practice firing their weapons.

"I had 66 men under me. What was amazing is that they put me in charge of artillery when I had been trained in '28 in radios. It made no sense. Of my men, we lost 40 on the first day. We fired our one or two shells per gun, then hid in ditches the best we could. The Germans came forward with tanks. One of my men got up. We told him not to. He was almost immediately sliced by a projectile, ripping his arm of along with that side of his chest. We got to him just in time to see his heart pump a few more times before he died. The Germans saw our men hiding in the ditches and drove their tanks with one tread down the ditch crushing our men as they went. It was terrible."

"What did you think of the Germans? Were they faceless guys or did you hate them or did you think of them as being just like you guys that just happened to be on the other side of the river fighting for the enemy?"

At first his response is emphatic, but then his tone changes to a more conciliatory one. "Ah oui. But you know, it doesn't do any good. There was a guy who was afraid of nothing. So one day he had to go to the water." He pronounces it like "What-air" as the French often refer to the toilet. "He got up and went to do his thing, and they picked him off. I think he died right away. So you can see, we really didn't try to communicate. We went down to a chateau named St. Creutzwald (ed. about 20 miles east of Thionville and touching the German border) in the middle of the night, and had a funeral service, a mass, etc.

And all of a sudden, the curee came forward and presented himself to me. It was a friend of mine from EOR. When I saw him, I said "Mon viex Trevilli" to which he replied, 'Ah mais dittes dont, c'est toi!' and we embraced each other like old buddies. I told him to stay with us. I said 'you're going to stay and we'll all eat. Just because there's a war on doesn't mean that we can't eat.' Later that night we all returned to Thionville." His eyes twinkle and he smiles as he speaks. He's on a roll now, animatedly chattering as one thought flows to the next.

Several days later at Villiersville (spelling?) I asked him, 'What are you doing after all this is done?' He didn't reply but asked me the same thing in return. I told him, 'I'm going to start a brick factory. And you?' 'You're going to laugh,' he said. 'I'm going to become a priest.' And we had just walked down that street several days earlier. I told him that I was happy that we had we had walked together. It's funny, isn't it?"

"After the war," he continues, "I had to go to Caen, in Normandy, to go see a brick factory. And the stuff I wanted was ready, but after that, I asked for the curee since I knew that he was from there. The lady told me that he was in the hospital. And I wrote afterward. I got news from him, but he had already died. Anyway, that night during the war, he wondered what I was doing there. It was just the two of us at dinner with a couple of servers. We saw each other from time to time after that.

I brought the conversation back to the combat. "So on which day were you attacked?"

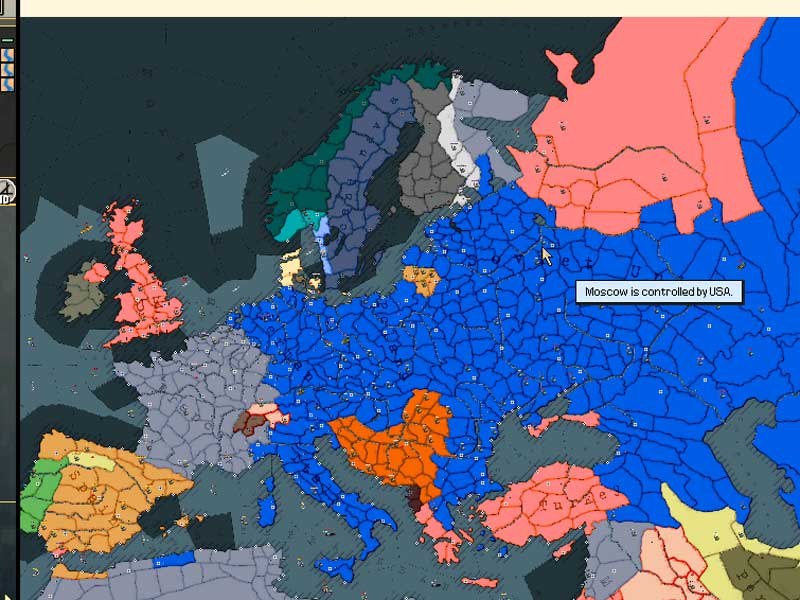

Eh bien, we were... when they passed through here," he makes a sweeping gesture across the map over Belgium, "we were over here," tucked away in the northeast corner of France near the Maginot Line. "They were encircling us, coming from in back. So we fell back on La Fause/La Faux (phon: "lapho" (sp?), Soissons, etc. Let's see, Nancy, Bar le Duc, it's around here somewhere." He searches with his index finger until he finds what he is looking for. "Here, Soissons. It's here that I stole the bike."

"What was the bike for?"

"Well, I stole a bike." He seems a little sheepish admiting that, even if it was during a time of war and anything useful like that was being destroyed by the invaders or being carted off by the masses of refugees. "I was demobilized at Charos sur Cuisse on the river Cher. So anyway, I came back to see my parents. I had brought my little suitcase with my civilian clothes. It arrives that I come to Charos and a policeman redirects me to be demobilized.

He says, 'Mon Vieux' and he starts hassling me. I was in my civilian clothes. I opened my suitcase which had my uniform inside, stripes and all and I took it out saying, 'You know, we just got slaughtered for people like you and you're now giving me a hard time for demobilizing. I took out the uniform, ripped off the stripes and threw them at him. And I had one or two more stripes then he had. Ha, ha. So if you'll now just leave me be. I'm not asking you for anything except that you sign my release papers, that's all. I'm going to find my wife and my parents who aren't far from here. But if I didn't have stripes, if I hadn't been an officer, they really would have given me a very hard time."

The French had been retreating. Grandpapa said that as his unit fell back, they overtook the refugee columns clogging the road. And at that time, he had seen his parents, my grandmother and my uncle somehow and somewhere - I don't remember ever getting the details from him. Grandpapa had asked his commanding officer if he could join his family. His officer said 'yes' on condition that he bike back to his unit the next day. So he did, finding his family again and spending the night with my grandmother. And then, true to his word, he pedaled back to find his unit the next day. He and my grandmother joked that my Mom was conceived that night, though assuming that it was June, 1940 and she was born at the end of the next year would have meant an incredibly long gestation period.

"The war ended about June 22, '40. So when were you demobilized?"

"Yes, we were demobilized eight to ten days after the armistice signed between Germany and France." That ignominous chapter in France's history saw Hitler in Compeigne, France bringing the humiliated French officers to sign their surrender in the same railroad car where their German and French predescesors had signed the end of World War I just 21 years earlier. Hitler danced his victory jig (which was later shown to have been fabricated by some clever film doctoring) and then ordered the railway car moved to Berlin as a war trophy. The wagon disappeared during World War II, but historians speculate that it was destroyed during one of the aerial bombings of Berlin. Today a near copy of the railway car sits in the museum built at the site.

My Grandfather won the Croix de Guerre. He joined the Resistance, though his role was subtle - a munitions runner using his truck. He travelled to Chateau Thierry, Reims, etc. He remained very closed lipped about the details saying only that he knew who had been in the Resistance and who had collaborated. But he never told me any of that. His own duties were hardly the glamorous activities of the movies - cutting phone lines, blowing up train tracks or using machine guns for ambushing Germans.

Then again, he was already 37 by this time, married and with two children; I can't imagine taking huge risks myself at that point. Instead, he would pick up shipments in one place and take them to another. The Germans never caught him though one of the German guards even hitched a ride with him at one point. I do not know why a German would have hitched a ride with him; perhaps it was simply to be social, to build goodwill or maybe just because they were probably older than the typical front line soldier and really didn't care as much about getting killed or killing.

The Germans in France were typically reserve divisions made up of older soldiers or of foreign soldiers (captured Russians, etc.). I suspect that if the German had wanted to get my Grandfather in trouble, he could have. That, coupled with other stories passed down in our family, have indicated to me that not all of the Germans were viscious SS types. A lot probably wanted the war over with and just wanted to get back home. In any case, they were probably happy to be pulling relatively light occupation duty when the alternative was to be shipped off to the Russian front - which was where 90 percent of the German soldiers who were killed in the war died.

Previous Page | Next Page

Robert Thibault, French Soldier

Robert Thibault, French Soldier, page 1, 1907-1997

Robert Thibault, French Soldier, page 2, 1928

Robert Thibault, French Soldier, page 3, 1939-1940

Robert Thibault, French Soldier, page 4 - Liberation of Coulommiers, France, August 27, 1944

Francais

Italiano

Espanol

Deutsch

Related Links

- United States Air Service in World War I at www.usaww1.com

- My travelogues of France, USA, Canada, UK, Japan, Saudi Arabia, etc.

- Thibault Villa

- 3rd Armored Division History Foundation

Keywords

12ème RA 1940

12ème Regiment 1940

12ème régiment artillerie 1940

8e Division

8ème Division D'infanterie

12ème Régiment d'Artillerie (3ème Armée, 8ème Division D'infanterie)

8ème Division D'infanterie infanterie

Phoney War

French army, 1939-1940

EORs, Eleve Officiers de Reserve

Quentin Roosevelt

1st Pursuit Group

American Air Force in France

American Air Force World War I

3rd Armored Division

Robert Thibault

Alcee Thibault

Raymond Thibault

Louis Thibault

Louis Toussaint Thibault

Louis Guyot

Titi Regnier

Regnier, Meung sur Loire

Home

Home Hearts of Iron

Hearts of Iron

French Military Victories...

French Military Victories...